The Old World Underground — Day’s Cottage Cider and Perry, Brookthorpe, Gloucestershire

“I just about recall the first time I drank cider,” Dave Kaspar says while ladling out a bowl of homemade vegetable soup in the farmhouse kitchen of Day’s Cottage. He hands it over then pours me a glass of deep-red, press-fresh apple juice. “It would have involved getting completely pissed in South London on something unspeakable.”

Should the name Day’s Cottage be familiar, the odds are high that you’re either partial to hyper-locally produced cider and perry, or based in the same pocket of rural Gloucestershire as the Cottage itself. Here, tucked among wooded hills on the pheasant-flown fringes of the Cotswolds, Dave and his partner Helen Brent-Smith oversee 20 acres of shaggy, traditional orchards. When you wander the lines of apple trees it feels like pacing through a slower, older world.

Photography by Ben Lerwill

In many ways it is. The couple and their small team have been working with fruit here for almost 30 years, although many of the trees—those planted by Helen’s great-aunt Lucy—have been in place for more than a century. Step forward to the present day and Day’s Cottage (which is the name of both the family home and the drinks business) is a hands-on local producer of juice, cider and perry for farmers’ markets and festivals.

As Dave outlines, we live in a country where teenage encounters with cider tend to be low-grade: cheap, fizzy-sweet rotgut sloshing around in garish plastic bottles. Although, in more recent times a raft of new and interesting cidermakers are changing this narrative. But there were also exceptions in decades past—and you don’t need to stray far to find a notable example. Less than four miles away from the Cottage as the crow flies sits the tiny hillside hamlet of Slad, best known as the home village of the late Laurie Lee.

The author and poet set a benchmark for mid-20th century British literature with his rich, descriptive style. His lyrical 1959 memoir Cider With Rosie was foisted on many an inky-thumbed schoolchild as a set text, but it remains a vivid account of the writer’s childhood years. In it he recalls his own introduction to the sweet stuff:

Never to be forgotten, that first long secret drink of golden fire, juice of those valleys and of that time, wine of wild orchards, of russet summer, of plump red apples, and Rosie’s burning cheeks. Never to be forgotten, or ever tasted again…

This part of England, if you hadn’t twigged, is apple country. So much that on the centenary of Laurie Lee’s birth in 2014, Dave and Helen blended 100 different varieties—including one from the author’s former garden orchard in Slad—to create 100 gallons of a commemorative cider named Rosie’s Kiss.

It sold out quickly, fitting neatly with the overall Day’s Cottage ethos. Each batch produced here is a one-off, and when it’s gone, it’s gone. In other words, if you’re searching for consistency and uniformity, you can take your flagons elsewhere.

“We grow more than 200 varieties just on the farm, and about 50 or 60 of them are cider apples,” Dave says. “It means we’re constantly experimenting, and that’s what keeps it exciting. You know, if we’ve got Kingston Black—a fantastic variety, a really lovely rich bittersweet cider apple—and we fill part of a barrel with that, you can’t leave it empty, so you fill it with something else.”

““We grow more than 200 varieties just on the farm, and about 50 or 60 of them are cider apples.””

“To be honest, sometimes it’s just practicality,” Helen adds, as we approach the converted dairy that now acts as a juicery-come-cidery. Their adopted rescue dog Mischa potters around close by. “You might have two trees next to each other, which are both ripe at the same time and you think, how will they do together? Let’s give it a go.”

The ciders and perries are all strong (“it’s all wild natural yeast, and whatever strain it is we have here means they always come out around 7.5%.”) The first batch I try is predominantly made up of an apple variety called Pedington Brandy. It’s hazy and golden, sparkling gently in the glass. The mouthfeel is crisp, wine-like, and smooth, with a long finish that mellows into a soft, farmy fruitiness.

“The weather is never the same two years running, so there are so many variables,” Helen continues. “All our trees are unsprayed. Some years you’ll get a bumper crop from one and the following year get nothing. It means the blends and mixes we do are always different. One year you’ll get a load of sunshine, which will create different sugars in the fruit, and one year you’ll get a load of rain. So you never know what you’re going to get.”

She gives a wry smile. “Although from a commercial point of view, you’re not supposed to say things like that anymore.”

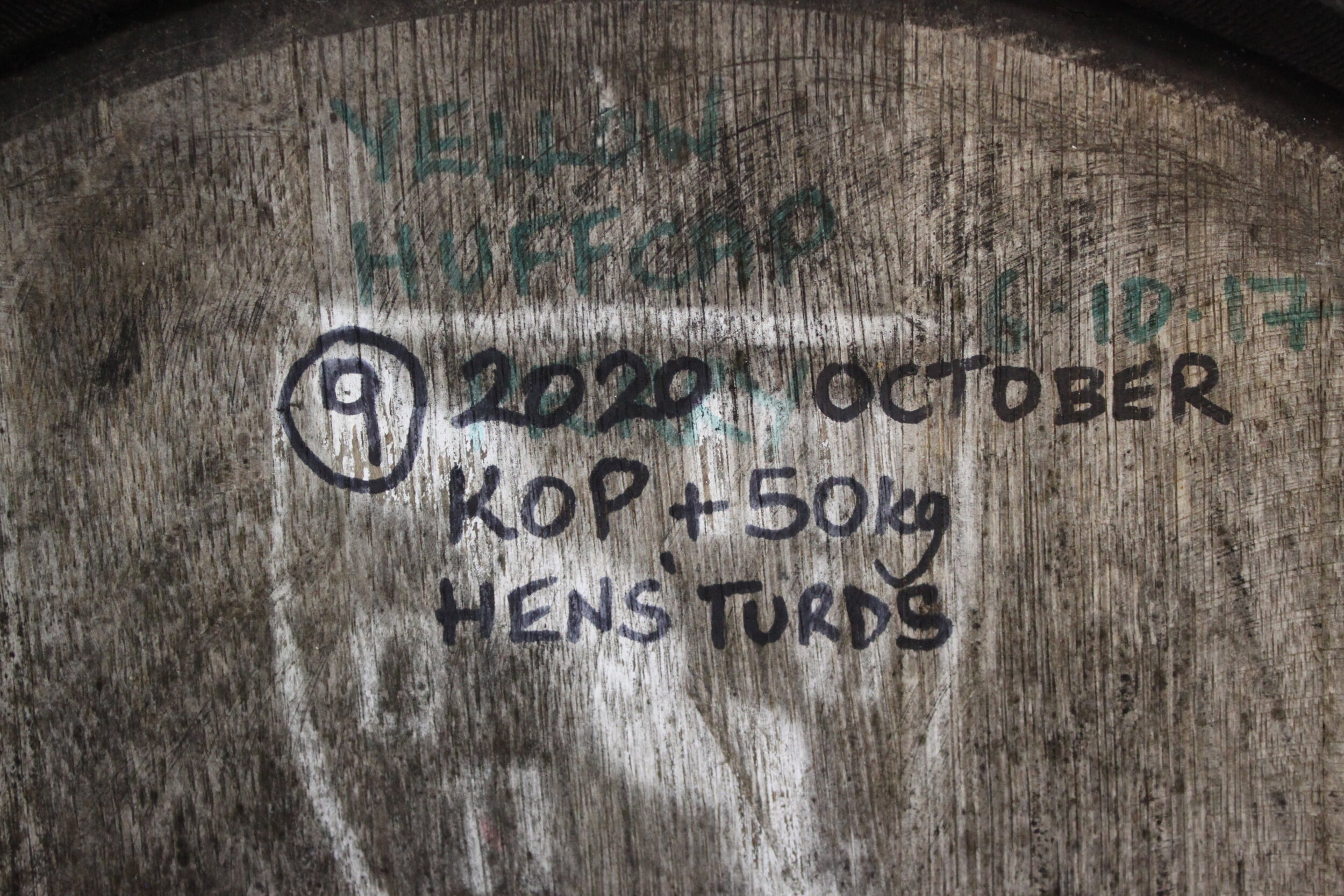

Don’t mistake this improvised approach for a lack of hard work. Dave and Helen are elbow-deep in jobs from the moment I arrive, as is the four-strong team of young, good-humoured employees. I’m here in October, which means trees are being picked, apple-stuffed cheesecloths are being pressed and bottles are being labelled. The yard is full of pallets, crates and fruit. Second-hand barrels sit in what were once cow stalls, fermenting 40 and 100 gallon lots of cider and perry.

Helen’s family have lived in this area since 1794 (“bloody newcomers” jokes one of the workers,) but it was fate that led to today’s set-up.

“Thirty-one years ago I was a language teacher in South London and Helen was a clinical psychologist at Guy’s Hospital,” Dave tells me. “When we met, we were basically just getting hacked off with being consumers—we realised our lifestyle was wrong. When the opportunity came to move down here, we took it. Although frankly, where apples were concerned, I knew nothing.”

You can learn a heck of a lot in three decades. In that time, Dave and Helen have not only replanted 20 acres with traditional varieties but have set aside space for a so-called Gloucestershire Museum Orchard, which grows around 80 varieties indigenous to the county. The whole thing is a bona fide labour of love. Across the acres, apples are growing in an astonishing range of different colours, sizes and shapes. Some of the fruits cluster in berry-bright bunches, others droop fatly on slender branches. They range from burgundy-red to lemon-yellow, and from cannonball-hard to eminently chompable.

And oh, the names! They read like a fevered opium dream. King of the Pippins, Siddington Russets, Arlingham Schoolboys and Hens Turds. Slack-ma-Girdles, Taynton Codlins, Hagloe Crabs and Mrs Sylvie’s Cow Apples. Bastard Underleaf, Nine of Diamonds, Dainty Maids and Jackets & Waistcoats. The good news for drinkers is that they taste as individual as they sound: all crunch and juice, with autumn-fire skins and singing white flesh.

The amusing apple names can also bely the fact that what’s going on here is essentially a conservation effort. Conservation is a word that gets bandied about a lot these days, but here it’s the right one. A countryside-first, money-second approach underpins everything Day’s Cottage stands for. They’ve planted more than a kilometre of hedgerow, and their acres support some 50 species of birds—including little owls, nightingales and all three species of British woodpecker—as well as nine species of bat and countless invertebrates. And in a fine example of mutual benefit, local beekeepers have no less than 30 hives on site.

Where the future’s concerned, Dave tells me about an extra perry orchard they planted five years ago in an outer field. “It’ll be in its prime in the 23rd century,” he says, with a that’s-how-it-has-to-be shrug. I try a batch of the existing perry, made with an old variety named Brandy. It’s fresh and lightly pétillant, with a full flavour that swirls from earthy to sweet. The taste, like the fruit, is one that belongs to these hills and orchards.

“We see what we do as an art rather than a science,” Helen says, as we watch newly picked fruit being pressed. “There’s a load of as yet to us inexplicable things: that’s the art to it. The other year we had two big barrels of perry from the same pear, from the same orchard, picked on two consecutive days. One barrel was ready by Christmas, three months later, crystal clear and absolutely beautiful. The other one stayed milky-hazy for months into the next year.”

For many producers, this would be seen as a headache. Not here. You get the sense, in fact, that the unpredictable alchemy of natural drink-making is precisely what keeps them motivated.

“Depending on your viewpoint,” says Helen, “what we’re doing is either the absolute end of people doing things this way or—with everything that’s going on in the world—it’s the absolute example of how things are going to have to go.”