Lying Snowblind in the Sun — The Inherent Whiteness of British Beer Writing

Not many people encounter profound thoughts when filling in an application form.

I was joining the charity Beyond Equality, which was seeking volunteers to take part in workshops to challenge schoolboys’ gender stereotypes. It required the usual personal information, but I had a sudden realisation about my life when I was asked to detail my experiences of workplace diversity. The truth is, I have little first-hand knowledge of interacting with colleagues who look like me or who were from a similar background. My father was of Indian origin and my mother is Malaysian; neither were educated to degree level.

Despite not thinking of myself as an outlier, I am. This explains why I prefer freelancing: I like choosing what to write about, and I get to avoid being managed by someone unsympathetic to me. Instead, I seek out like-minded editors but even so nearly all the people I get commissioned by are white. Even more problematically, all my British contemporaries who work for beer publications are always white.

Journalists are used to calling out industries that lack diversity but rarely is the same scrutiny applied to the one they work in themselves. But they should look inwards, because the figures are stark.

According to a recent National Union of Journalists (NUJ) report, 92% of British journalists are white. This will come as little surprise to writers of colour like myself, who have worked in UK newsrooms where it’s easy to become sidelined by the dominance of a white monoculture. Worse still, Black journalists represent 0.2% of the total, and little has changed since a similar survey was conducted in 2012.

Somewhat embarrassingly, drinks journalism is one of the lowest-performing sectors for representation of people of colour. We make the United States look more progressive, especially if you consider that two of the most revered beer books The Oxford Companion to Beer, and The Brewmaster’s Table were written by Black writer and brewmaster at Brooklyn Brewery Garrett Oliver.

I may not be as charismatic as Garrett, and wouldn’t even necessarily class myself as a beer writer. I am a member of the British Guild of Beer Writers but I also derive most of my income from writing about other subjects, such as TV, film, and video games. I do care deeply about beer and pubs, though, and enjoy putting together stories that challenge readers’ perceptions.

When I wrote this piece on racism craft brewers face in the beer industry I was surprised that such a bold investigative report requiring a lot of time, guidance and investment was given the green light, considering it was the first story that I had approached Pellicle with. But why am I one of the lone minority voices who write about beer compared to other sectors, like food, which sees far more writing from people from diverse backgrounds?

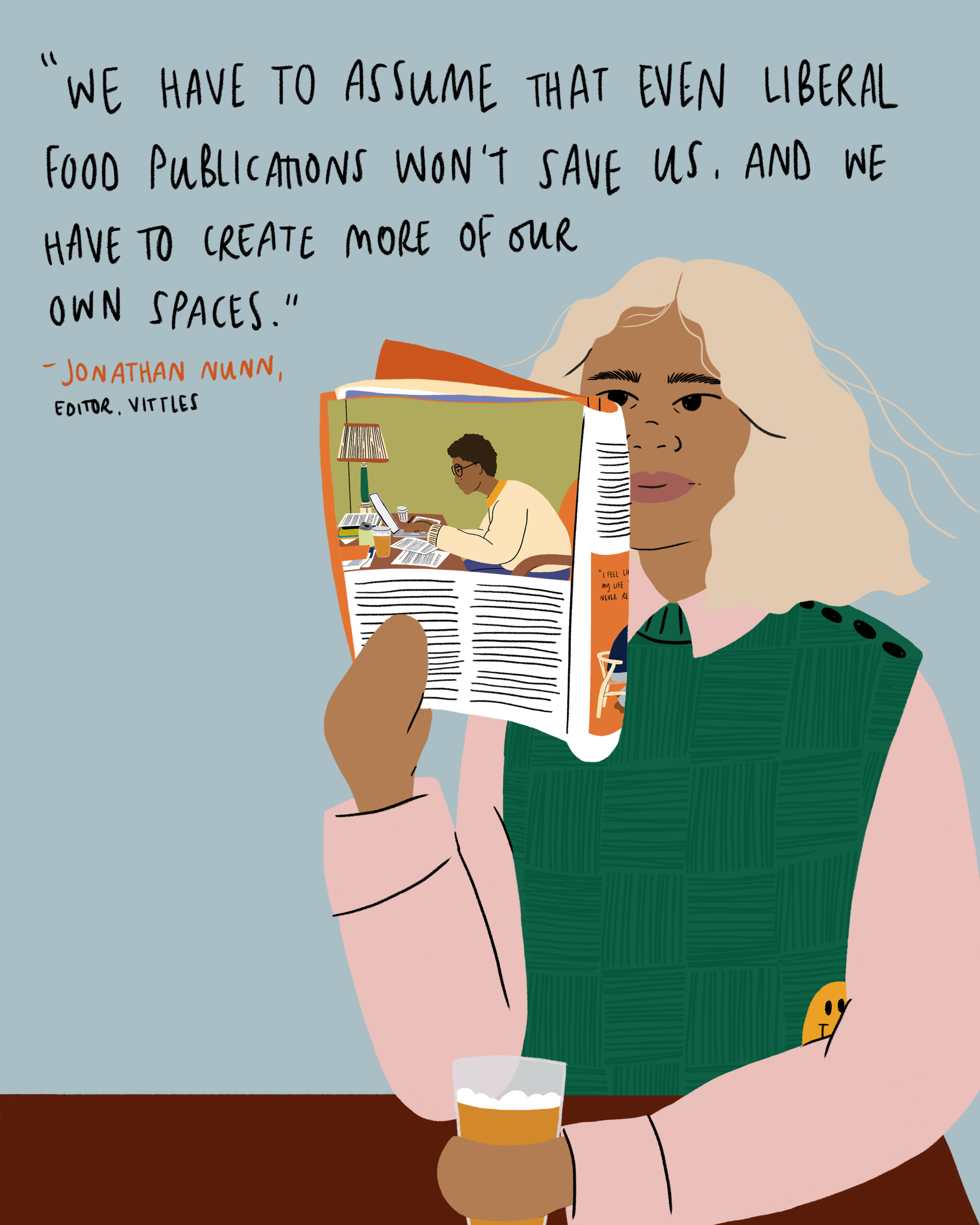

Jonathan Nunn runs Vittles, a food periodical based on newsletter platform Substack, and is one of the few non-white commissioning editors I work with. He receives a high amount of pitches from people of colour—more than 50% he tells me—which is staggering. Pellicle, co-founder Matthew Curtis reveals, will obtain only around 5% of story ideas from non-white writers.

Illustrations by Sophie Parsons

“I imagine that’s to do with the fact that diversity within food writing is reliant mostly on those with non-white British backgrounds to use their family history and their culture to talk about food, and, in a way, translate that culture for an audience which, it’s assumed, doesn’t understand it,” Jonathan tells me.

“So there’s that opportunity there, although often it doesn’t go beyond that, or there are certain cultures not deemed even important enough to bother translating,” he continues. “However, with beer writing, even though beer has a very diverse history and present, I don’t think that desire for translation is there.”

In my experience, I have found that if you look in the right places there is a desire for translation but that comes with one big caveat: I often find the publications that have the biggest resources and pay the most aren’t interested in the type of story I would write.

In fact, the reason I worked with Jonathan was that the Guardian ignored my pitches for this deep dive into why Black youngsters were being ignored by the farming industry. Conversely, Jonathan was keen to invest in the story and understood the difficulties I faced in getting it published.

“This is a problem with journalism in general,” Jonathan says. “Cuts to budgets mean that you tend to have the same roster of voices given opportunity again and again.”

“In food journalism that means the same recipe writers, the same critics, the same drinks writers. They have to be the voices that all culture passes through. I understand the logistics of it even if I disagree with it, but that means we have to assume that even liberal food publications won’t save us, and we have to create more of our own spaces.”

Using the same voices means it’s easy for a publication to appear diverse by giving opportunities to one writer of colour, but that usually leads to that one journalist taking all the work. I’ve at times benefited from this, and I do notice I have a high hit rate with video game pitches that focus on race.

But I do think this is a conversation worth having within beer writing and requires some hard questions being asked similar to the ones that were posed by the Bon Appetit controversy in the US. It was a watershed moment for food writing and the racist behaviour of Bon Appetit’s then-editor-in-chief Adam Rapoport spurred a debate—the scale of which is yet to happen in drinks journalism.

Pete Brown is a veteran beer writer, and the outgoing chair of the British Guild of Beer Writers (BGBW), so is well placed to discuss why this timely conversation hasn’t happened in the UK.

“Our brewing cultures are totally entrenched in Northern European origin,” Pete says. “It's historically confined to where barley grew better. And so it’s a tradition that immediately looks white European because that’s its origin.

“The next bit I don’t want to get wrong because I’m conscious of my white privilege and not knowing exactly where it extends to. But craft beer wants to be more open and inclusive, so it’s kind of embarrassing for craft beer, in its very loose community sense, that non-white people aren't well represented. Because we’d love it if they were.”

Matthew at Pellicle agrees with Pete on this issue of history and the origins of beer in the UK, but points to the progress made in terms of more women and LGBTQ+ people forging careers as journalists (last year women outnumbered men as winners in the Guild’s annual awards). He is honest about the work that still needs to be done.

“Beer writing has not acknowledged its whiteness,” he says. “Because it’s never been asked to.”

***

“I do have regrets because I feel like sometimes I’ve wasted a lot of my life trying to get into an industry which never really wanted me.”

Marverine Cole is explaining to me the struggles she faced when she first became a journalist after graduating in the late 90s. She imagined a TV career based in her home city of Birmingham during the height of Pebble Mill studios but found that she faced obstacles being a Black woman.

Despite these challenges, she went on to become a successful TV presenter at Sky News, ITV and the BBC. More recently she’s won awards for her beer blog, Beer Beauty and is a regular columnist for BBC Good Food magazine. She’s also director of the BA journalism course at Birmingham City University, making her ideally placed to speak about the industry she had difficulties breaking into due to her skin colour.

“People don’t like talking about race in this country,” Marverine says. “Look at the report [by the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities] which said ‘everything’s fine!’ When it isn’t.”

“It takes an organisation to be bold to change things. If I had more of a platform then I would love to be bolder. I don’t think youngsters are aware that beer writing is a viable career because they don’t read newspapers or magazines, they get everything from Twitter or WhatsApp.”

Marverine thinks one way to reach her students—which have a diverse makeup reflective of the Birmingham catchment area—would be for the Guild to overhaul its award categories which currently favour print media and target influencers and bloggers.

“In the five years I’ve been teaching and lecturing no one’s ever said: ‘can you help me become a food or drink writer?’,” Marverine says.

Travel journalist Hannah Ajala is equally honest and readily admits that UK journalism is institutionally racist because it never “initially factored in” anyone non-white. She works for the BBC and helps black journalists network through her We Are Black Journos project.

“When we look at publications like Condé Nast Traveller, or Lonely Planet, I've never come across a piece by a non-white traveller showing their views of racism because it’s just not their style,” she says. “But I’m grateful to know other incredible platforms where I could openly share those experiences with. So if I really felt compelled to share that, I would look for a publication that will be able to share that with me 100% speaking my truth.”

Hannah has a simple fix for the publications that seek diverse writers, but are inundated with pitches from journalists from more traditional backgrounds.

“I do not have a problem with an editor saying ‘hi, I’m looking for an amazing black writer…’” she says. “They can get straight to the point because these are keywords that people can search for on Twitter.”

Marverine and Hannah both derive a lot of their income from non-traditional media. In my case, I gain 100% of my income from print and beer writing, which I can attest does not generally pay well.

Jobs that appear glamorous, like writing about alcohol, often favour people from more comfortable backgrounds who are more likely to be white.

Pete Brown is perhaps the number one beer writer in the country, with a string of acclaimed books to his name. But what he has to say on this issue was quite daunting.

“I’m chronically in debt,” he says. “And always worrying about how to pay the mortgage from one month to the next. So if I’m in that position, what’s it like for someone trying to get into the industry?”

Print media was once well paid, but since circulation started dwindling rates have plummeted and beer writing pays around, or just below, the current market rate. If it’s difficult for Pete, then it’s even more financially demanding for me and it’s only fair to disclose my earnings.

Last financial year I gained just enough income to pay tax which, aged 42, is pretty abysmal by any metric, especially as I have two small children to support. Yes, my earnings were severely affected by the pandemic and I had to look after my daughter when her school closed—but it also explains why I currently live in a very small flat, don’t own a car and live pretty much hand-to-mouth most months.

But there are months that I do earn a decent living, especially when I write personal essays and if I were to chase more of these I would be in a more comfortable position. This kind of work favours interesting backgrounds, like mine, which means non-white journalists can potentially earn well from the industry.

Pitching work that pays well means coming into contact with people who could be inundated with story requests and more often than not, folks in these positions are white because most management roles are likely not to come from a minority.

“It’s less of an editorial issue,” says Hannah, who only pitches to people who are sympathetic to race issues. “But more of a recruitment/HR one.”

“Why is it a constant, repetitive cycle of just being white people in these spaces? And if it is a non-white person in a senior role, that’s because it’s better suited for the audience demographic, for example, BBC 1Xtra.”

***

Four years ago the North American Guild of Beer Writers (NAGBW) realised they had a problem with diversity and formulated a plan to try and make the field more accessible. Now, in the US, budding beer journalists from backgrounds similar to mine can apply for a grant to help them support themselves.

“The creation of the grant came about simply because it was the right thing to do,” Bryan Roth, director of the NAGBW says. “If we were going to recognise that stories about diversity, inclusion and equity were important, we needed to find a way to step up and support that by trying to identify ways to give opportunities to people who had traditionally been under-represented and under-served in journalism.”

The grant is offered to anyone from a diverse background and the funds are paid out when a story is written. At the moment the guild pays a very competitive $0.50 (approx £0.36) a word for a digital article, and Bryan tells me he has commissioned two stories this year of 2,000 words each.

Along with commissioning new writers and handing out the grant, Bryan will help numerous unsuccessful applicants to re-tweak their pitches so that they can be offered work elsewhere. It sounds like hard work—Bryan will receive more than 40 pitches each year—but ultimately it’s rewarding.

“I can say that today that we have the most diverse collection of members that we’ve ever had,” he adds. Although diversity figures are not currently kept by the NAGBW or its British counterpart.

It’s a great idea. So much so that I’m going to commit one of the most frowned upon crimes in journalism: I’m going to commit plagiarism. I want to set this grant up in the UK and I’m more than happy to volunteer to get it up and running.

I’m doing this because it should be run by someone who knows what it’s like to be of colour and struggle in an industry when white is the default. I want to use my experience of dealing with white gatekeepers and help fledgling journalists gain the work they deserve.

I don’t want to work in an industry where only 0.2% of people are Black. It’s time that we did something about institutionalised racism.

“I've started to think,” Matthew at Pellicle says. “We have to be proactive, because the whole point of beer writing and drinks writing is to make the culture more open and understandable to people.”

“And by having more writers from different backgrounds it becomes a window,” he says. “A bridge. We need to do what they’re doing in the US because beer writing [in the UK] is too white.”