White Light, White Heat — Allagash Brewing in Portland, Maine

Rob Tod and Jason Perkins of Allagash Brewing are far from home, but hardly out of place. They’re set up in the attic of Brasserie Cantillon in Brussels for Quintessence, an intimate festival where brewmaster and owner Jean Van Roy brings in a few like-minded breweries every other year.

Servers stationed behind upturned barrels are pouring a range of Allagash’s beers, brought from Portland, Maine, on the northeast seaboard of the U.S. Rob, the founder, and longtime brewmaster Jason are standing off to the side, in a quiet eddy of the crowd, half-hidden among the roof’s beams. Not many passers-by seem to recognise them, standing there in Allagash-embroidered plaid shirts, but they are beaming as they chat with the well-wishers who do.

Photography by Ben Moore

“I never thought I’d have the opportunity to come back and pour our beer, right next to one of the legendary coolships in the industry,” Rob says when I join them. He’s nodding at the corner where Cantillon’s cooling vessel sits just under the roof tiles. “It never gets old.”

Pilgrims climb a few wooden stairs from the attic floor to gaze into the wide, open-topped pan of patinated copper. On brew days in the cooler months, this is where the alchemy of lambic begins as fresh wort is exposed to ambient microbes—wild yeasts and bacteria including Brettanomyces Bruxellensis, present in the air, and in the fabric of the brewery itself. Once cooled overnight, the wort goes into well-worn barrels (typically ex-wine but also cognac and other experimental barrels) where it picks up further fermenting microorganisms on its way to becoming a Cantillon beer: a lambic distinguished by its sourness and a character as close to wine or cider as it is to the rest of the beer world.

Rob and Jason are in this attic, by this coolship, because they have one of their own back home, albeit made of stainless steel rather than copper. Theirs, highly regarded in itself, dates to 2007—reportedly the first in the U.S. to attempt the much-fêted Belgian method of spontaneous fermentation.

It was an experiment inspired by one of Rob’s visits to Cantillon—thus his comment about ‘coming back’ to pour his beer. In 2006, Rob joined a group of American brewers on a tour they dubbed “A Tribute to Belgium”. Among them was Vinnie Cilurzo, the founder of Russian River Brewing, who has presented at Quintessence twice alongside Allagash.

That was not Rob’s first visit to Cantillon, but it was a pivotal one. He came away with the seemingly sacrilegious idea of trying it at home. Jean had insisted that it could be done in New England, not only—as Belgian lore would have it, and as lambic purists still maintain—in the valley of the river Senne.

Soon after, Rob and Jason began asking questions. While many lambic brewers might be inclined to guard their historic processes to preserve exclusivity, Jean was forthcoming. There were no real trade secrets to reveal, but he answered technical queries about temperatures and cooling procedures, gravity measurements, fermentation timings, topping up barrels, and such.

“There are no textbooks out there [for this kind of beer],” Rob says.

“He urged us to be patient a lot of the time,” Jason recalls of those early email exchanges with Jean, as their initial batch was slow to begin fermenting and showed little development over the first year. It took nearly two years for the characteristical ‘Brett’ flavours to reveal themselves in the beer. “I still bounce questions off him while I’m here.”

““I wanted to do something different, and I looked at Belgian brewing tradition as an opportunity to do that.” ”

As Jason explains it, their approach has been to replicate (as closely as they can) Cantillon’s ingredients and processes—but with the idiosyncrasies of spontaneous fermentation, this is hardly a copycatting effort.

“We control as much as we can but there’s only so much control possible,” he says.

***

Rob and Jason’s studious patience came good. Not only for what Jason calls the surprise success of that first batch, but in building from those lessons learned into a broader programme of spontaneously fermented beers.

The exemplar of this range is Coolship Resurgam (Latin for “I shall rise again”), which combines one, two, and three-year-old spontaneously fermented beers. Out of deference to both Belgian brewing tradition and strict style and naming conventions, Allagash declines to call this blend a gueuze, or its spontaneously fermented beer a lambic. Nonetheless, the comparison is undeniable.

Resurgam’s aroma of musty cellar hits me like a traditional gueuze. Of course, as I taste it I’m standing in the close atmosphere of Cantillon, but I’ve had this impression of Allagash Coolship beers from past encounters, including the previous summer sitting on the brewery’s front terrace in Maine.

The first taste is tart but not puckering with acidity. There’s a range of malt flavours, rich with apricot and gentle citrus. It rides a round and fulsome yet light mouthfeel. There is also a spicy, tannic note that distinguishes it from the Cantillon that I’ve just tasted—a special Quintessence blend of two-, three- and four-year-old lambic—nonetheless, that note is more a distinction than an aberration, as the Allagash remains nicely rounded in keeping with the traditional style.

“It’s a success because, for me, Resurgam is one of the best spontaneous fermentation beers,” Jean tells me as we sit in one of his tasting rooms at Cantillon, during preparations for Quintessence. “It’s probably the closest beer, from spontaneous fermentation, to lambic.”

That sensibility shines through in Allagash’s other Quintessence offerings, including Coolship Pomme, a two-year-old spontaneous beer that rests for four months on a selection of local apples. What comes through is not so much the fruit or juice, it’s the taste of apple skin, contributing to that tannic spice and balanced tartness. It remains interesting all the way to the bottom of the glass.

Honey Berry Tumble—an alcopop-sounding name that nearly put me off trying it—surprises with the character of a young kriek carrying an extra dose of vanilla. There is a sweetness there, but it’s complicated like wildflower honey, with a bright acidity to keep it from cloying.

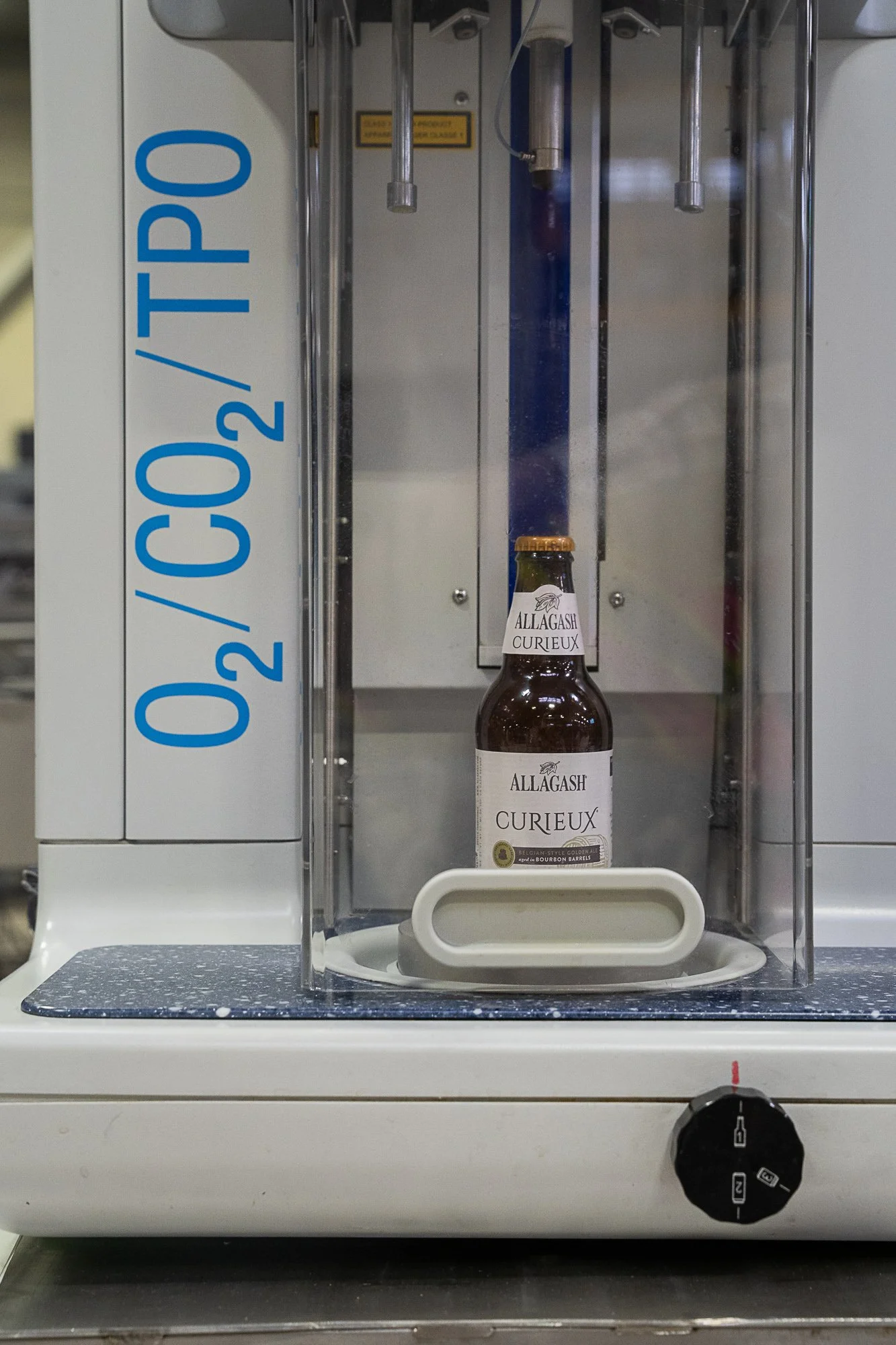

Curieux is a barrel-aged version of Allagash’s Tripel, which is a deadly easy 9% ABV with the brightness of candied tropical fruits and apricot, plus a Belgo-yeasty tang and effusive carbonation. With its time in a bourbon cask, Curieux takes on a layer of vanilla and a liquory feel but remains quite drinkable for its 10.2%.

“Subtle complexity and balance” is Allagash’s doctrine, as Rob explains when I visit the summer before Quintessence, in August 2021. It’s a line that could come from many of the great brewers of Belgium.

Yet in that conversation we’re sitting on a picnic bench, surrounded by conifers on the outskirts of Portland, Maine—“Forest City,” as locals have called it since 18th Century colonists cut timber for the Royal Navy. It makes quite a contrast from Cantillon in an industrial section of Brussels, or even the more rustic lambic breweries amid the open fields of the Pajottenland just west of Brussels.

Rob’s affinity for Belgian beer goes back nearly 30 years, when he was washing kegs and learning the rest of the trade at Otter Creek Brewing in Vermont, another wooded state in New England. Part of the early wave of craft breweries in the region, it was best known at the time for its Copper Ale, a sort of American Altbier, not that many of us knew the Düsseldorf original.

Otter Creek typified the U.S. craft scene of the time, working mainly from English or German influences. Brewpubs were starting to pop up, but the idea of flavourful, interesting beer came from Europe. To Rob, Celis Brewery’s White embodied that idea.

This witbier hails from Austin, Texas, but essentially carries on the family business of Pierre Celis. A former milkman from Hoegaarden, in Flemish Brabant east of Brussels, he saved his hometown’s indigenous beer: the citrusy, coriander-spiced wheat beer that now defines the style. After selling the Hoegaarden brand to Interbrew (now AB InBev), he brought his heritage and knowledge to the US, setting up with his daughter Christine in the Texan capital in 1992.

““For me, Resurgam is one of the best spontaneous fermentation beers.”

”

Around 1993, someone handed one to Rob, and he was struck by its pepper and citrus-peel aromas, with its unmalted wheat lending a tartness and creamy mouthfeel. It may not have been his first taste of the style, but the Celis resonated with Rob as he was searching for his own path. He went on to set up in Maine, where there were around 15 breweries at the time, dabbling mostly in German and British styles.

“I wanted to do something different, and I looked at Belgian brewing tradition as an opportunity to do that,” he recalls as we speak at his brewery.

Nothing about a Flemish wit is overwhelming. Everything depends on balance in a thirst-killing brew resting around 5% ABV. As Rob puts it, “It’s a very sessionable beer.”

So, in 1995, Rob converted some dairy equipment into a brew kit and began dialling in his own White.

***

It was New England’s original hazy beer, creamy with wheat proteins, decades before the rise of New England IPAs with their characteristic cloudiness.

In an elongated, Allagash-branded tulip glass, White shines not clear yet translucent, a tinge darker than Champagne, perhaps a shade darker than Hoegaarden. It looks more like a sparkling lemon juice than beer, topped by a meringue of snow-white head.

Compared to a classic blanche (as we call a wheat beer in the francophone parts of Belgium), Allagash’s brings a bit more hop kick, with a herbal aroma and pithy bitterness. It sits a bit softer in the mouth—that’s saying something, for a style brewed with 20% unmalted wheat—but remains a clean-finishing and more-ish beer.

Witbieren are famously characterised by the addition of fruits and spices. Particularly as Allagash handles them, applying coriander and Curaçao orange peel in the Hoegaarden manner, with a light touch. The ingredients don’t stand out individually per se; they meld into a complex but approachable beer.

The drinking public took years to find and embrace this subtle, satisfying but initially unfamiliar beer. Over those first four years or so, Allagash was all in on White, making little of anything else before Jason came aboard in 1999 to help broaden the range. Rob meanwhile stuck with his vision of selling the beer he liked best, almost entirely on draft, even when sales were slow and mostly local. He humbly credits Blue Moon with normalising cloudy beer, thanks to the marketing muscle of Coors, now MillerCoors.

It took perhaps a decade, but White ultimately found its place not just in the beer-hunters’ bars but as a staple in New England’s restaurant scene. Witbier’s citric freshness and subtle acidity pair perfectly with a range of food, including the seafood the region is known for. Style and tradition matter to some drinkers, as Rob tells me over glasses of White at his brewery, but not as much as simply having a great beer over a meal with family. “That’s what’s more important to people.”

The James Beard Foundation, promoter of the culinary arts in America, named Rob its Outstanding Wine, Spirits, or Beer Producer in 2019. That recognition speaks to Allagash’s place in the wider community alongside its many brewing laurels—such as its eight medals from the Great American Beer Festival, including its fifth gold in the Belgian-style Witbier category in 2022.

As we sipped one on the patio outside his brewhouse, Rob allowed that White has gotten more consistent, from its dairy-equipment beginnings to the German-built, state-of-the-art works it’s now brewed on. This is exactly what he wanted back in 1995, he declares.

“This is still my favourite thing to drink, and it’s not gotten old at all.”

White was Allagash’s only beer in the early years, and it’s still about 80% of production, Rob notes. “We wake up at four in the morning on Monday and make Allagash White around the clock until Thursday.”

***

Allagash has widened its range in various directions over recent years. The Coolship beers—helped by constructing a separate facility for these experimentations—have added a great sense of play, with diverse fruits and barrel treatments. They include Cerise, which faithfully represents a kriek without appropriating the name, and even an ‘Estate’ version with cherries grown on the property.

Together in Spirit, in the style of a tart Flemish red, pours from its cork-and-cage bottle with a mahogany hue and tastes of sour cherries, redcurrants, and black raspberry. There are impressions of treacle going on to burned molasses, all kept in check by assertive acidity.

Allagash brews several takes on saison and an array of wild ales—as Allagash calls those that don’t depend entirely on yeast entering via the coolship, but are instead infused with Brett, or other souring microorganisms by other means, such as placing them in an unsterilised barrel. Others are products of mixed fermentation, involving both wild microorganisms and conventionally pitched yeast. Plus umpteen perfectly made pale ales and lagers in various grain bills. I could while away the short Maine summer at that picnic table trying them all.

The brewery, which took some years to branch beyond its flagship witbier, nowadays works up more than 100 new recipes a year on its 45-litre pilot setup. Any Allagash employee can try out an idea on it, as Rob—never one to describe himself as the auteur—frequently explains.

Referring to the coolship, barrel programme, and fruity experiments, he adds, “That’s like one percent of our sales but fifty percent of our culture.”

Allagash’s Belgian immersion extends to the whole team, with a yearly (Covid aside) tour for staffers reaching five years’ service. Rob credits the ideas to New Belgium Brewing in Colorado, but he’s made it a part of Allagash culture.

The “Bellagash” trips sample rare bottles at Cantillon with Jean, and has visited mainstays like the Trappist abbey-breweries of Chimay and Orval, micro pioneers such as Brasserie d'Achouffe and De Dolle Brouwers, and the newer guardians of the heritage like Brasserie de la Senne and Brouwerij Hof ten Dormaal.

“The brewers learn a lot about traditional brewing techniques, traditional brewing equipment,” Rob explained in yet another conversation in Belgium, in April 2018. We were sitting at a cafe awaiting the start of Nacht van de Grote Dorst (“Night of the Great Thirst”), a lambic festival where Allagash was for some years the only American represented.

But the visits are “cultural exposures,” he insisted, not a technical seminar. “Any experience here may get someone’s creative gears turning.”

***

Allagash has influenced plenty of other creators back home, including Dan and David Kleban.

When the homebrewing brothers were dreaming up a business plan, they cold-called Rob. He didn’t know them but offered advice over a glass at The Great Lost Bear, the local craft beer institution that was the first to sell White. The Klebans went on to set up Maine Beer Company in 2009, just across the road from Allagash’s grain silos, in a low cinderblock building that has incubated several other thriving breweries.

“They were very outgoing, offering us advice and support—if we ran short of ingredients, lending us some,” Dan says. As newbies to commercial brewing, they called on all manner of technical knowledge from Jason, like how to count yeast cells and take oxygen readings. Maine Beer, now based up the coast in Freeport, has gone on to wide recognition for its powerfully bitter IPAs.

“Stylistically we probably couldn’t be further apart in a lot of ways, but in how you conduct yourself, how you run your business, I obviously took a lot of cues from Rob,” says Dan. “To this day I look to Allagash as a brewery that does things the right way.”

A bit further up the coast in Brunswick, Nate Wildes founded Flight Deck Brewing in 2017 with a mission to make his eclectic mix of hoppy, spiced and fruited beers as green as possible, using only renewable energy.

But plastic piles up, from the shrink wrap and bags carrying ingredients, can holders and the like. Those may be recyclable but not in the “standard stream” picked up at the curb.

“You need volume,” Nate says. So Allagash takes in smaller players’ recyclables with its own, shipping plastic wrap and such a couple of hours south to Boston. “It improves the sustainability of the industry.”

““They’ve really been the kind uncle of the brewing industry. They want what’s best for everybody,””

Allagash also has helped bring material into the brewery. Flight Deck uses almost all local ingredients—a commitment made possible only because of the bigger brewery’s own pledges, such as buying a million pounds (nearly half a million kilograms) of grain grown in the state each year.

“It seeded the industry and gave [farmers] a big customer to grow for,” Nate says. He’s quick to add, the point is not quantity—Maine produces plenty of barley for animal feed—but the quality Allagash needs for its grain-forward beers. The impact reaches beyond the fields to local maltsters, fruit growers, and more.

Allagash also has shared its know-how with future brewmasters by collaborating with the nearby University of Southern Maine in building a lab for brewing quality.

“They’ve really been the kind uncle of the brewing industry. They want what’s best for everybody,” Nate says, in developing “a world-class ecosystem” for good beer. “They’re encapsulating the quality of Maine.”

A vibrant craft beer scene is the sort of attraction that helps draw people from bigger metropolitan areas--something Nate thinks about in his other job, as executive director of a promotional agency called Live + Work in Maine. Allagash, he says, has helped “attract talent to Maine, not only talent in brewing but talent in business.” Allagash seems, then, not only a kind uncle to the brewing industry itself but to the state around them.

***

Along its journey, Allagash became the state’s largest brewer, at close to 120,000 hectolitres per year as of 2021, according to the business news outlet Mainebiz. Countrywide, that ranks 23rd among craft breweries, according to the Brewers Association. The pandemic in the spring of 2020 was foremost a life-and-death matter, but it hit Allagash’s draft-intensive business particularly hard, shutting restaurants and bars across its top markets.

“Seventy per cent of our business instantly went away on March 16th,” Rob recounts of the previous year in our conversation at his brewery in August 2021. “It was scary.”

They recouped what they could with a high-speed canning line installed, by chance, just months earlier. That investment aims to bring Allagash to more occasions, like people grabbing a rack on their way to a barbecue or, as, Rob puts it, in the most Maine way possible, when going canoeing. Yet it entailed not just new equipment but a revamping of supplies, production, marketing and sales.

“We compressed a three-to-four-year effort into three months,” Rob says. “It was an all-hands-on-deck effort, and it went well.”

That new sales channel covered just half of the lost draft sales. But thanks to government relief for employers, Allagash eked out its cash and made payroll for the staff, which numbered 140 as of late 2021. Otherwise, Rob says, “We would’ve had to lay off a lot of people”.

Allagash has lived to fight another day. Its experiments will continue, just like its canning line has helped reach people in new ways. Describing where Allagash is going now, Rob looks back to the beginning.

He speaks about its early years focused on White and then—drawing a Y in the air with his hands—branching out to its many areas of experimentation. “I can see us going in lots of different directions.”

“The Belgian brewing spirit will be core to what we do,” he says. That, he elaborates, refers to “this openness to make beer with different raw materials and different techniques”—fruit and spices, different fermentation and grains, various types of barrels.

“That approach to beer is different,” he says. “It’s not a culture that’s there to chase trends. Don’t hold your breath on us doing a hazy,” he says—which is not to say he doesn’t like some of them—or other things like a line of hard seltzers.

But ultimately Allagash is not about a particular portfolio of beer styles, Belgian or otherwise. “Our culture is giving people new experiences with beer,” Rob says. “Just like with White.”