Lève ton Verre — What’s Left of Coreff, France’s First Real Ale

That’s the best seat in the pub, next to the fireplace, where you can listen to the gentle sound of crackling logs, benefiting from the warmth it gives off. Raspoutine, the pub’s gorgeous ginger cat, sleeps beside it. From the comfort of his pillow, he slightly opens his eyes when patrons approach him, then loudly purrs at any attention he receives.

Facing up to the bar, I like to observe who’s drinking what. Mostly, I’m counting how many people order a pint of cask ale. Three old guys buy half pints when Raspoutine jumps from the pillow onto my lap. A middle-aged woman gets herself one as well. The cat jumps from lap to lap around the table as another guy orders a pint.

That’s an unusual thing to witness here in France. A place that feels like a British pub without trying to mimic it. Where you can order a real ale straight from the handpump and enjoy it by the fire. Not a real ale imported from England, either, a French one.

Ty Coz (‘old house’ in Breton, as the building dates from 1452) is one of the few places that still serves it. Based in Morlaix, North Brittany, it’s also the first one who did.

***

For decades, the pub window displayed the following inscription: “At Ty-Coz, first draft of the famous COREFF Real Ale, Morlaix’s beer.”

The story goes like this: One beautiful day in May 1985, the first Coreff was served by Roger Le Jan to Fañch le Marrec. Pictures of that first drinker regularly come up on the brewery’s social media, where the Breton musician proudly stands in front of Ty Coz toilet door, painted with the first Coreff logo.

Called Brasserie des Deux Rivières when Jean-François Malgorn and Christian Blanchard opened it in 1985, Coreff is considered France’s first microbrewery.

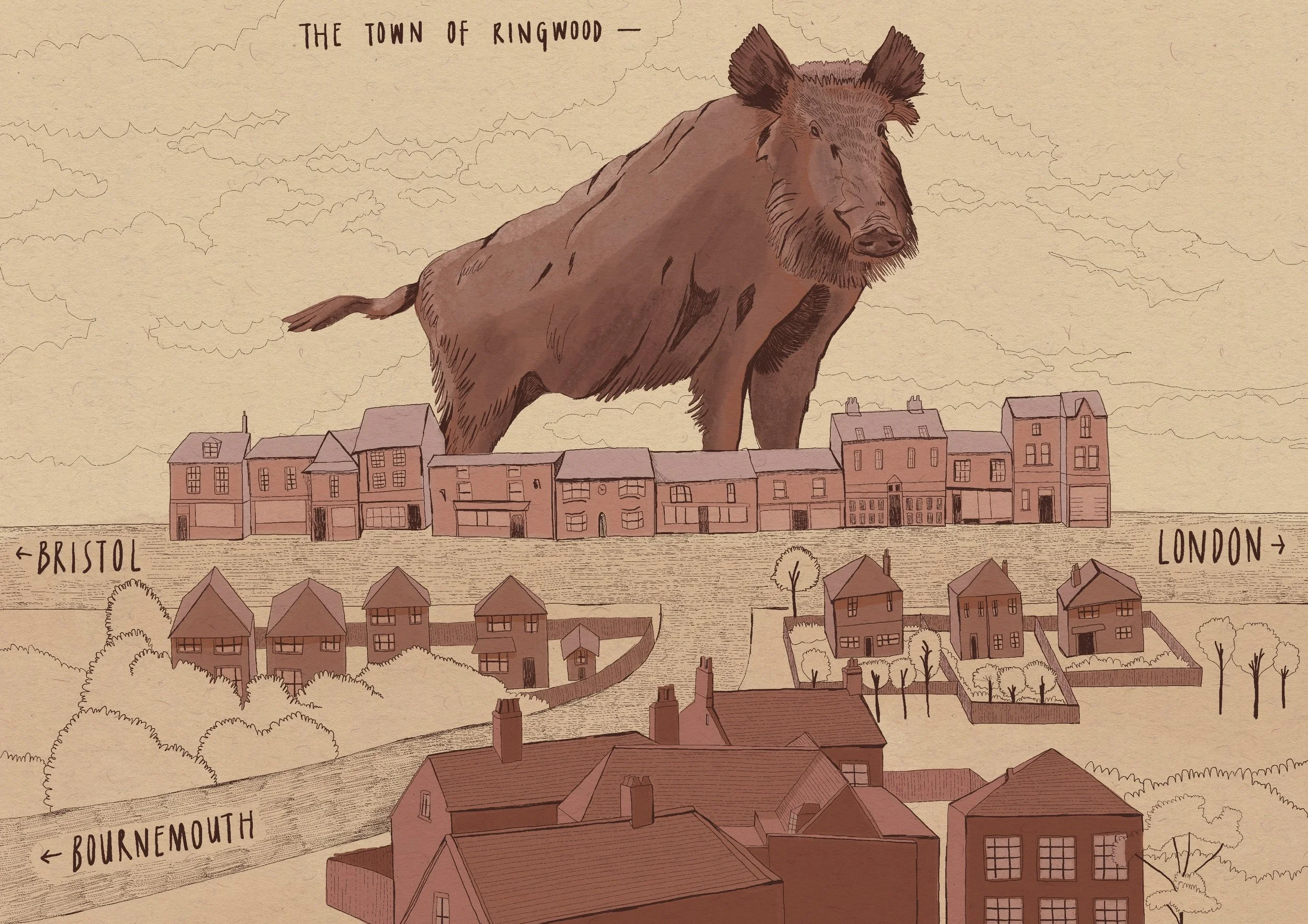

Illustrations by David Bailey

Brewing nothing but real ale at the time, Coreff came to life with the help of a person that will mean nothing to the vast majority of French people, even the beer drinking type. Yet he’s considered a legend on the other side of the English Channel: Peter Austin, founder of Ringwood Brewery in Hampshire.

“If some dare to call me the pope of microbreweries, today, I can claim the right to appoint Jean-François Malgorn and Christian Blanchard as my disciples,” Austin wrote in a 1988’s commercial leaflet recalling his partnership with the brewery. “What a journey, how much work we did to offer you the only French Real Ale: Coreff!”

(Editors note: sadly the original Ringwood Brewery was closed in January 2024 by current owners Carlsberg Britvic.)

***

I check out my pint on the wooden table, a bit grumpy that it’s been served cold. I think about how many confused French people bringing their warm pint back to the bartender it must have taken for pub owners to collectively decide to serve it that way. Only a few venues still keep it at cellar temperature.

I also wonder how Coreff’s l’Ambrée historique—the name advertised in most bars—has managed to stay afloat for four decades, and even exist in the first place.

Coreff’s origin story wouldn’t raise any eyebrows if it happened today: two friends discover beer, fall in love with it and leave their desk jobs at the bank to open a brewery.

““Beer culture in France was drinking 250ml of a yellow liquid with bubbles in it.””

But it’s not so banal when you take into consideration that it happened in the 1980s, in a country with less than 50 breweries still open (most of the industry being owned by big brewers like Heineken,) and that the beer they wanted to brew was a bitter conditioned in cask, which didn’t exist anywhere in France.

“Beer culture in France was drinking 250ml of a yellow liquid with bubbles in it,” Matthieu Breton, Coreff’s owner since 2008, tells me. “And then there’s Jean-François and Christian, coming with a warm flat beer, brown like manure.”

Jean-François and Christian discovered real ale in Carmarthen, Wales, in 1979. And when they decided to go into brewing four years later, despite everyone around them telling them not to, their Welsh friends pointed them towards Peter Austin, over at Ringwood Brewery.

“The momentum for real ale was becoming widespread, even in America,” Northern Irish brewer (and trailblazing founder of the former West Coast Brewing Company in Manchester) Brendan Dobbin says. He recalls meeting the Breton duo in 1983 at Ringwood, not surprised that they wanted to bring it over to France as well.

As expected though, considering French people's affinities with sweet, strong Belgian beer and bubbly macro lagers, the first pint of Coreff was a whole new experience, and not always a good one.

“Everyone was asking ‘how’s the Coreff today’ when entering the pub and even if landlords never said it was bad, you knew its condition by the face they were making,” Matthieu remembers with a laugh. “No matter the answer, we were going to order it anyway.”

To accommodate French people's taste, Jean-François and Christian quickly lowered its bitterness level. Then, Matthieu filtered it—the beer, though, still uses the famous Ringwood Yeast, as do most of the brewery's other beers.

While Coreff didn’t settle anywhere in France, it opened in Brittany, a place with a strong attachment to preserving its Celtic culture and supporting its people. From the very beginning, Jean-François and Christian could count on local pubs’ unconditional support for their work.

For Matthieu, it’s this early endorsement from pub owners that has helped Coreff make a name for itself and grow. “At the bistrot, landlords used to say, ‘You can have a local pint or a shitty international beer’ so the choice was all made,” he says.

One of these loyal pubs is Tavarn Ty-Élise in Plouyé, a few miles from Carhaix-Plouguer, where the brewery moved in 2005. There you’ll only find Coreff’s beer, from the real ale to the IPA and the nitro stout—the latter is “totally Irish in recipe formulation,” according to Brendan.

Élise Provost is not surprised to learn I’m here specifically for the real ale. “You’re not the only one,” she says with a grin, as she points to a group of grey-haired English guys drinking pints by the open fireplace. “They say they crossed the Channel this weekend to come here.”

She serves me a beautiful pint, at cellar temperature, as I sit down next to the Englishmen, ready for their second round. Coreff got some attention from across the Channel when it launched. In the book Coreff: Légende, a press clipping mentions the visit of 14 CAMRA members at the brewery in 1994, while the beer won several real ale contests in Jersey and Guernsey.

Over the years, Brendan pursued the partnership Peter Austin started. In 2019, he helped install the brewhouse at a new brewing site near Nantes, then advised on new equipment in Carhaix in 2020. “I still help any old customers as they wish,” he says, as he travels to Brittany regularly. “We’re friends for life!”

***

Today, if you stumble upon a handpump at a French bar, you’re almost guaranteed to be served Coreff’s Real Ale—the British pub chain Wells & Co still has a few bars serving cask ale, as well as a couple of venues aimed at beer connoisseurs—but it wasn’t always that way.

“I was raised with Coreff,” Xavier Leproust tells me. In its wake, Coreff influenced a generation of Breton brewers like him: in 1998, he founded An Alarc’h (“the swan” in Breton) making his own cask ale.

“ “At the bistrot, landlords used to say, ‘You can have a local pint or a shitty international beer’ so the choice was all made.””

“With Brasserie de la Soif and Brasserie de Pouldreuzic, we were a few to follow what Coreff was doing,” he says. “It made sense at the time, but they’re both closed now.”

Outside of Brittany, attempts at making British style ales or real ale was sporadic, but not nonexistent. “Peter Austin set up breweries in Lille and Clermont-Ferrand, but they both closed,” Brendan adds.

In 1998, he helped brasserie Alphand in the French Alps, and a brewpub in Paris. The first one brews all kinds of beer styles from Belgian ales to Irish stouts while the other stopped being a brewpub a long time ago.

Then, in the first guidebook about French beer published in 1998, The Beers of France, writers Keith Rigley and John Woods mention another real ale producer: La Petite Brasserie Ardennaise, close to the Belgian border.

“René Bertrand made a bold move on 14th January 1998 when he opened a tiny brew-pub which uses an English brewing kit, to brew English style ales dispensed by hand-pump,” they wrote.

L’Oubliette, a pale ale, gets three ticks out of three from the writers, who see it as a “very interesting variation on an English ale. Strongly hopped but not bitter. Served in perfect condition” (Coreff’s real ale gets two ticks and is described as “smooth and surprisingly quaffy [sic] for its strength”).

The beer still exists but hasn’t been conditioned in cask for years, though the current owners were unable to explain to me why.

British beer heritage didn’t manage to thrive beyond Brittany’s border for various reasons, going from French people taste buds to a rude competition. “Back in the 90s, we didn’t have sufficient distribution strength to compete with big brewers and Belgian imports,” Xavier says.

Nowadays, new competitors coming from across the Atlantic with aromatic hop bombs may have put an end to any remaining hope for traditional British beer styles of breaking into French territory. Then Brexit came along and struck the last nail in the coffin.

“It became way too expensive to buy British raw materials with Brexit,” Xavier says, admitting he can’t afford to buy Maris Otter malt anymore. Even if he still focuses on British beer styles at his new brewery Ar Broc’h (‘The Badger’) with an amber ale and a dark mild in his core range, Xavier stopped making cask beer.

“It’s too complicated to keep making cask beer, as most bars don't have the place for handpumps or care about it anyway,” he says with a sense of regret.

“British beer is a niche in France, and it will always stay that way.”

Matthieu agrees, aware that Breton’s attachment to the brand and historic pub owners' protectiveness of the beer has made their real ale a staple in the region.

“It’s a hard beer to make and a hard beer to serve,” he admits. “But it’s still one of our best selling beers, we’re not getting rid of it anytime soon.”