Northern Exposure — Donzoko Brewing Company in Newcastle Upon Tyne

Reece Hugill rounds the corner at the wheel of his boxy white van. He’s come straight from delivering beer, a job he’s been pretty much solely responsible for since founding Donzoko Brewing Company six years ago.

Between crisscrossing the UK to supply customers, Reece has also moved his brewery three times, across two countries. In the last year alone he’s collected lorry-loads of brewing kit off a street in central Vienna (after a brief foot chase) and poured lager for out-the-door queues in Tokyo.

Evidently, the road has been long and winding since Reece, fresh from university, decided to chase a particular beer memory and make it his own. Today, under cobalt skies in Newcastle upon Tyne, he opens the door of his new brewery-taproom and tells me the “soul” of Donzoko now has a home.

***

Ouseburn is a small, formerly industrial valley on the east side of the city, teeming with creativity. Overlapping streets slope towards the paddocks and plots of Ouseburn Farm, while artists’ studios, music venues, and food and drink offerings are perched around an inlet of the River Tyne.

Photography by Matthew Curtis

Donzoko is just up from Stepney Bank Stables, which means that while Reece’s brewery is only a 15 minutes walk from central Newcastle, two lines of ponies clip-clop by as we reach his front door. It might be interesting to know the ancestry of those horses, since Reece discovered—after signing the lease—that his building sits directly above a section of Hadrian’s Wall.

For slightly more recent history, a stroll to the end of the road reveals the broad metal brow of the Tyne Bridge, which was constructed in 1925. Reece is from Middlesbrough, some 40 miles south of Newcastle, and both his grandads worked on this magnificent structure, once the longest of its type in the world.

Though he’s from a family of steelworkers, Reece decided to launch Donzoko after the plant which employed his dad and uncle closed down. North-eastern heritage remains important—it’s something he’ll channel through Donzoko’s new taps—but the inspiration for what he now calls his “life’s work” came from further afield.

While studying chemistry at Newcastle University, Reece spent 18 months working and travelling in Germany through 2014 and 2015. One thing he learned: he didn’t want a career in chemistry.

“I was a bit stuck,” he says. “Like, what do I want to do? I went through a period when I was a bit depressed about it.”

Unexpectedly, clarity arrived on a trip to Munich’s annual Oktoberfest. The way Reece tells it reveals much about his attitude towards his vocation.

““He’s a genuine innovator... No barrier is too big—he seems to be able to take anything on with the same enthusiasm.””

“Oktoberfest is the worst place for beer,” he chuckles. “But seeing that many people so happy—even though it’s a bit of a pantomime—made me think: I do like beer; I have made beer at home… It’s kind of just chemistry you can drink.”

Beer being joyous is something Reece returns to throughout our conversation. When he describes one particular drink, an unfiltered lager he tasted at a Munich brewpub during his time in Germany, his voice quickens with enthusiasm.

“To me it tasted as hoppy as a cask pale, it had the drinkability and crispness of a lager—it was everything you’d want in a beer.”

Reece prefers not to name the beer, because he’s visited the brewpub since and found its characteristics had changed. But right then, as an overseas student, his ambition was fixed.

“I didn’t want a brewery,” he says. “I wanted to make that beer.”

***

Having done some homebrewing, Reece felt certain about his recipe: a Franconian-style lager made with Bamberg malt, natural carbonation, and natural acidification. But achieving this wasn’t going to be easy for someone who had “no customers and no experience.”

Undeterred, he used grants to buy a single fermentation tank and installed it in an outbuilding in Hartlepool, near Middlesbrough. Or, more specifically, in the former P.E changing rooms of what had formerly been a school.

Such limited space and equipment meant Reece needed to brew elsewhere—often on the pilot kit at Cameron’s, a local family-owned brewery—then transport the wort [the liquid produced from malted grain and hot water] to his own fermenter.

When he told another local brewer of his plan to open a lager brewery, the response was derisive: “Why?”

“The first tankful I made, a guy who owned a pub in Newcastle told me it tasted like BO,” Reece says, before clarifying that his first batch of beer did not taste like body odour.

Referencing the North East’s culture of cask beer, he draws similarities with Franconian lagers’ unfiltered nature, limited shelf life, and typical “party keg” packaging format.

“I wanted to make something completely different,” he adds. “Some people said it wasn’t a [traditional German-style] helles. I said it’s not: it’s Northern Helles.”

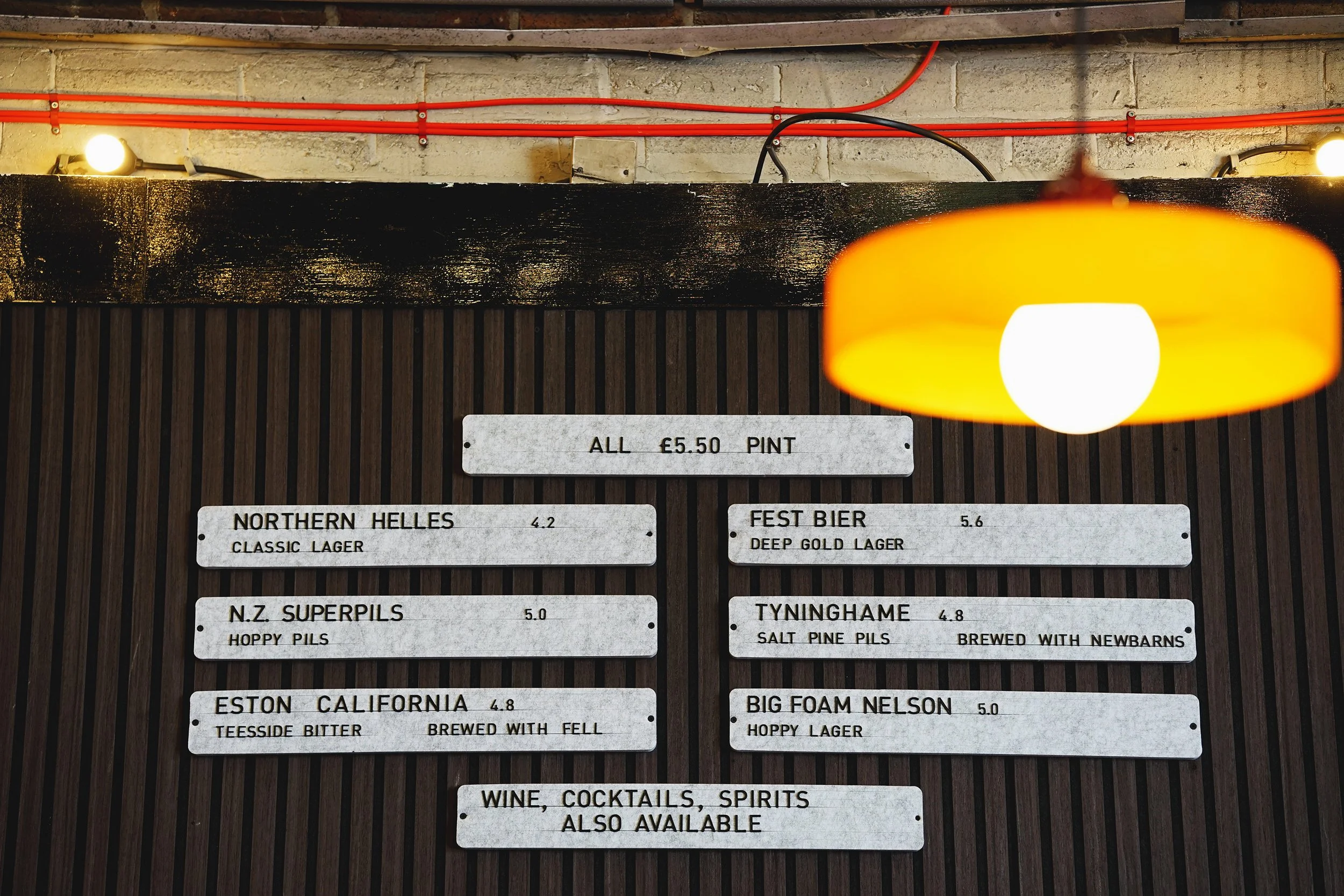

More than seven years later, Northern Helles remains Donzoko’s flagship offering. Halfway between bronze and gold, it brings a noticeable hop character balanced across malty sweetness and soft notes of lemon sherbert.

I enjoyed a couple of soothing pints in the Free Trade Inn, which overlooks Ouseburn and offers stunning views of the Tyne. In one example of circularity in Donzoko’s story, the Free Trade is where Reece officially launched his brewery in October 2016. Not only is Donzoko’s new brewery and taproom nearby, but Free Trade manager Mick Potts sent Reece the advert for the property as soon as it came onto the market.

By the start of 2017 Donzoko had acquired some local recognition, but building beyond that was proving tough. Things changed through a chance meeting in a Newcastle pub with Mark Welsby, owner of Stockport’s Runaway Brewery, and John Major, then of Runaway and now at Fell Brewery in Cumbria.

“They took some beer for their taproom, and soon I had a van going to Manchester every month,” Reece says. “Their kindness and proactivity got me out of a really tough situation, and possibly going under.”

Mark, who downplays the significance of Runaway’s role, had never heard of Donzoko before Reece arrived that evening with a beer delivery. As well as “loving” Northern Helles on first try, he recalls his impression of Reece.

“He was a very young guy,” says Mark, who has since stocked Donzoko at Runaway’s taproom and collaborated with Reece on the superbly titled lager My Neck, Maibock.

“It was quite amazing to see someone that young taking on something that brave,” he says. “Lager hadn't quite made it into mainstream craft beer at that time. I think people like Reece gave others the confidence to have a go.

“He’s a genuine innovator and I think his personality really lends itself to that. No barrier is too big—he seems to be able to take anything on with the same enthusiasm,” Mark adds.

The effect of that energy and expertise is something fellow brewer Zoe Wyeth points out, too. While working at Suffolk’s Burnt Mill Brewery in 2021, she made a dark lager with Reece after meeting him at a beer festival. Zoe remembers seeing Reece’s stall among ranks of hazy pale ales, sour beers, and imperial stouts, and being one of many drinkers on the day who loved Northern Helles.

“Reece is the kind of person you feel like you've known forever,” she says. “Super easy to get on with, friendly, kind. He's an incredibly passionate brewer and we had many geeky brewing conversations after that first meeting.

“Everyone at Burnt Mill was excited to collab with Reece,” Zoe adds. “We hadn't brewed many lagers at that point and were keen to learn from the best in the industry.”

In addition to Reece’s advice on how best to ferment the beer, Zoe recalls his preference for chit malt to aid head retention, something she hadn’t tried before but has used in all her subsequent lager recipes.

“The foam on the beer was incredible,” she says. “Dark Second came out exactly as we’d imagined and was a brewery favourite [while] it was around.”

***

While Reece remained the sole employee, Donzoko’s reputation grew and by 2021 he was looking to expand. Connections with other brewers proved instrumental again. This time it was a conversation with Gordon McKenzie, who, with his partner Emma McIntosh, was about to found Newbarns Brewery in Leith, Scotland (where Pellicle co-founder Jonny Hamilton is head brewer.) With space available in the Newbarns unit, Reece moved Donzoko 150 miles north.

While the surroundings and equipment were new, the type of beer he wanted to make hadn’t changed. By that stage, Northern Helles had been joined by (among others) Big Foam, which Reece describes as the “director’s cut” of the former.

The name hints at another enduring theme in Donzoko’s story, one which unites those elements of heritage and enjoyment: foam.

Reece smiles as he selects the right words to make his point.

“If you see a picture of a pint in your head…” he says. “Remember those sweets that look like pints of beer? They’re half foam!”

“It’s fun, it’s a sign of freshness and quality, it’s beautiful. That’s what I’m always trying to achieve, so my beer looks like a comic book beer for people. That’s what they’ll get at the taproom.”

““I want to keep true to what I want to put in the beer, but without alienating people.””

Drinkers at the “Home of Foam” (the phrase adorned Donzoko’s cans at the start of 2024) will also be able to access banked pints, a highly localised serving style from Reece’s native Middlesbrough and the surrounding area.

His passion for “bankers,” pints poured in stages so they arrive with a perfect bonnet of creamy foam, is evident in the way he speaks about them. In fact he lovingly articulated their significance in a piece for Pellicle published in 2022. Reece believes there are only a handful of pubs still serving beers this way, (although the article may have sparked something of a small resurgence.)

“It’s a regular, working-class thing,” he says. “It's not celebrated or promoted by the tourist board, so if it dies out, it’s not coming back.”

“If I can raise a bit of awareness to help keep it alive, that's cool. Because it's part of the story of the brewery.”

***

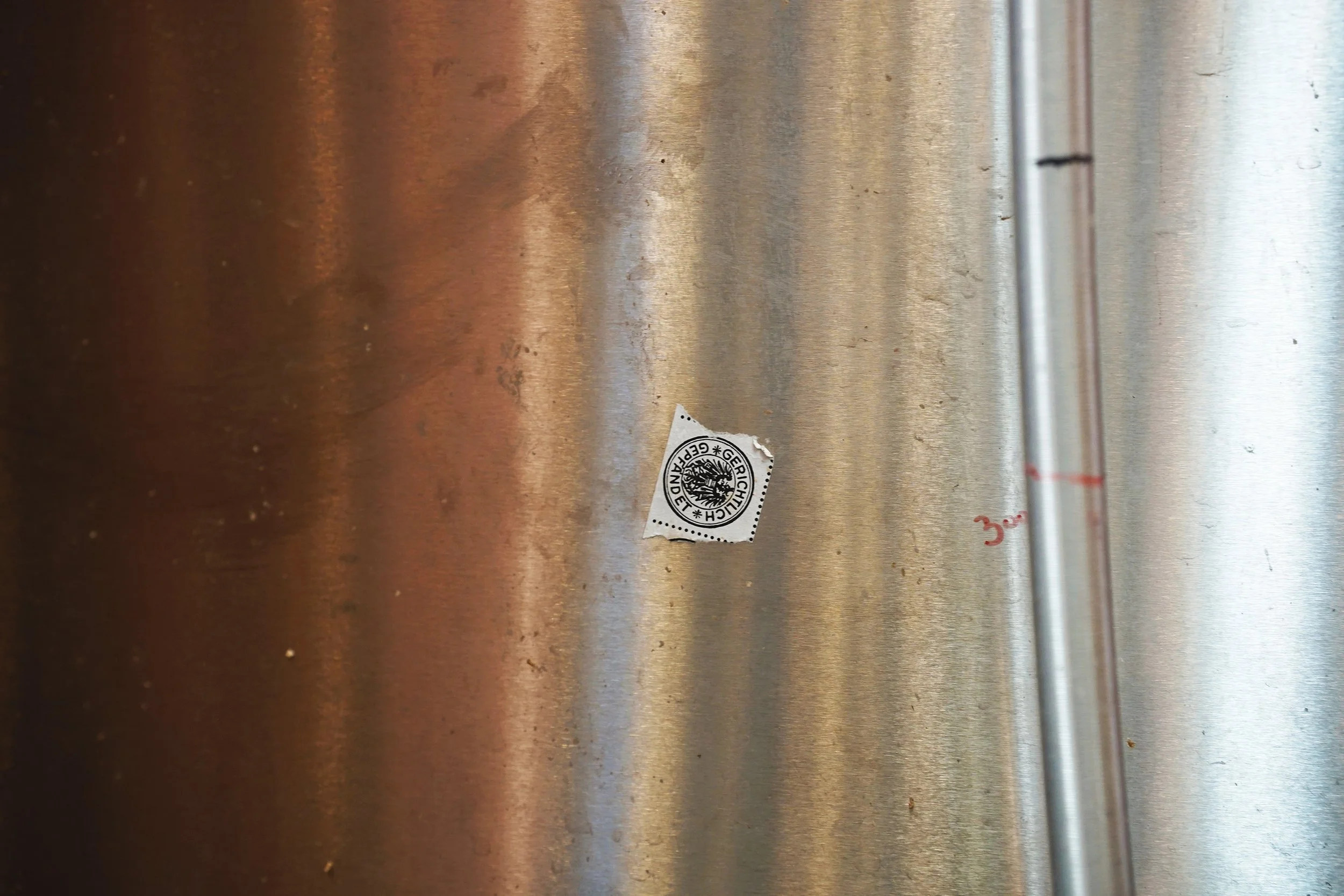

By summer 2023, Reece was searching for a brew kit of his own. Quite specifically he was shopping for second-hand equipment that had been manufactured and used in Germany. Something he hoped would put its own imprint on the beers he aims to make.

Following calls in pidgin German and some online bids, not long after the search began Reece found himself in Vienna, where gleaming copper brewing vessels and 13 fermentation tanks awaited him. As things transpired, the whole ensemble would spend two days outside on a city centre street, but, somehow, it miraculously remained unharmed and still in one piece.

Unfortunately, Reece’s finances were similarly static. A hurried call from the auction house revealed that, for reasons unknown, his funds had been blocked by the UK’s Financial Crimes Authority.

“I put the phone down and had a panic attack,” he says. “The head of the auction house was literally walking after me in Vienna, shouting at me.

“I said to my dad, who was with me: You know what, let’s go to a theme park.”

It was thus in The Prater, a large public park with a beer garden and ferris wheel, that Reece and his dad Rob found pints of Budvar, served with plentiful amounts of foam.

From there Reece managed to salvage the situation, and despite all the cross-border stress, he grins as he recounts a final detail.

“I ended up getting a payday loan for the brew kit,” he says. “When they sent the first bill, they included a voucher for online counselling.”

While his new brewery equipment migrated to the UK, Donzoko continued to established itself, while both the beers and Reece himself became increasingly well travelled.

A new addition to the range, imaginatively christened Train Beer—a 4.5% hazy pale designed for sipping as scenery slides by—is now a fixture on Lumo rail services between Edinburgh and London. Reece initiated the partnership by direct messaging Lumo’s managing director and proposing a new drinks-cart option.

Autumn 2023 saw Reece in residence at the hyper-compact Pigalle bar in Tokyo. Owners Hide and Chie Yamada had discovered Donzoko on a UK trip in 2020, thanks to a recommendation from Richard Brownhill, co-owner of excellent Leeds bar Brownhill and Co. Years later, Reece messaged to say he was due to visit Japan and suggested an event.

“We said we would really like to have cask helles, Franconia style,” Hide tells me, having seen on Instagram that Reece had poured his beer this way.

“No one imagined it would become the biggest party!”

The two casks of Donzoko’s Festbier were nail-bitingly held up in transit, but (potentially thanks to Hide’s prayers at a Shinto shrine), arrived just in time. 40 litres then disappeared in an hour, as scores of drinkers queued in the street to fill ceramic mugs with delicious, burnished gold lager. Served as bankers, naturally.

“Reece is a great brewer and wonderfully hospitable,” Chie says. “Lots of customers liked him and his beer; he was a big success in Japan.”

According to Reece, many drinkers at Pigalle were amused by the name of his brewery, as Donzoko can mean “rock bottom” or “loser” in Japanese.

“I was in a shed in a car park,” he says, smiling. “And now I’m in Tokyo with all these people drinking my beer.”

***

Back in Newcastle, Reece says the prospect of turning a large, high-roofed warehouse into a “comfy, welcoming” venue is scary and exciting.

When I visit before the opening, that space already contains plenty of metal tanks and —perhaps less obviously—some dark wood pews sourced from a church in Leeds, complete with thick cushions bearing embroidered dedications.

“I’ve had people tell me I don’t own a brewery because I don’t have a mash tun,” he says. “I’ve always had the soul of a brewery, but not the physical space.”

Before we sit down to chat in a more formal capacity, Reece tells me how he wants to produce and price beer which can be enjoyed by anyone.

“In brewing, you can be overly concerned about what people on [beer-rating app] Untappd think,” he says.

“I want to keep true to what I want to put in the beer, but without alienating people. If someone’s spent hard-earned money on a pint after work, I don’t want my lager to be completely off the wall and undrinkable [for them].”

In my experience, that approach extends to Donzoko’s non-lager options. The most recent version of No Problemo, a 4% ABV hazy pale ale, hit the bullseye between juicy and bitter. It’s a beer you could drink five of without really noticing, but afterwards your taste buds would be certain they'd had an enjoyable few hours.

Given the amount of effort Reece has poured into Donzoko, I’m struck by how he doesn’t appear to take himself, or beer, too seriously.

“Ultimately, it’s a fizzy drink,” he says. “But when beer’s really good it makes people want to socialise more; drinking less, but more often.”

“And when a space is good, people want to make it part of their community. I want to put the work into the liquid and the space, so it’s part of the community and people’s lives.”

“You have to do beer face to face.”