At the Crossroads — Big Fish Cider in Monterey, Virginia

Highland County, as its name would suggest, is found in Virginia’s mountainous western reaches, butting up to West Virginia. Located in the Allegheny Mountains, a sub-range of the Appalachians that stretches from Alabama in the Deep South to Newfoundland on Canada’s northern Atlantic coast, the county has one of the highest average elevations in the United States east of the Mississippi River. The county seat, Monterey, sits in the very heart of the region, at the crossroads of US Routes 250 and 220, and it’s here that Kirk Billingsley founded the award winning Big Fish Cider.

Born and raised in Highland County, the apple is core to so many of Kirk’s earliest memories, his parents boasting about a half dozen apple trees in their back garden. The mountains of Virginia are apple country. To this day orchards, groves, and single apple trees dot the landscape, some tended, some abandoned and now feral. Some produce famed heirloom varieties such as Ashmead’s Kernel, Roxbury Russet, and Virginia Hewe’s Crab, some are varieties whose names are lost to history, scions of seedlings that produced apples with too much acid and tannins for eating but perfect for drinking.

Photography by Mark Stewart

Each autumn, Kirk’s father would harvest his trees—amongst them a Northern Spy, a Grimes Golden, and a Winesap—pressing the fruit to make sweet cider, which they stored in a barrel. It was here that Kirk’s lifelong obsession with apples and cider began.

“I can still remember the scent hitting my nose, and the flavour just exploding in my mouth, and I still think fresh cider off the press is the best thing going,” says Kirk in his soft Virginian drawl. “I love the taste of apples, I love the smell of the bloom. My mom reminded me that I would come in and say if I could make a perfume with the smell of an apple bloom, I could be a millionaire. I never did make it mind.”

His father would tell young Kirk to wait for two weeks for the cider to be at its best. 14 days in the barrel and the cider would have started to ferment, and developed a spritz that highlighted the flavours of the apples. Kirk’s interest was further piqued when at university he learnt that his father hadn’t pressed cider that year, and so he bought a couple of gallons of sweet cider from the store to drink with his father on a trip home. His disappointment was palpable.

““I love the taste of apples, I love the smell of the bloom.””

“It was the most tasteless, insipid stuff I’d ever had in my entire life,” he tells me. “I was like, wait a minute, why is it cider that I make from these ugly apples that I pick off the ground around my house tastes so good and this commercial cider tastes so bad?”

Having returned to Highland County and a career in local banking, Kirk’s wife bought him an apple press as an anniversary gift, and he continued to use locally picked apples to make his annual fresh cider that he would provide to local stores and restaurants. As so often happens, the genesis of Big Fish Cider as one of Virginia’s pre-eminent, award winning cideries, was unintentional.

***

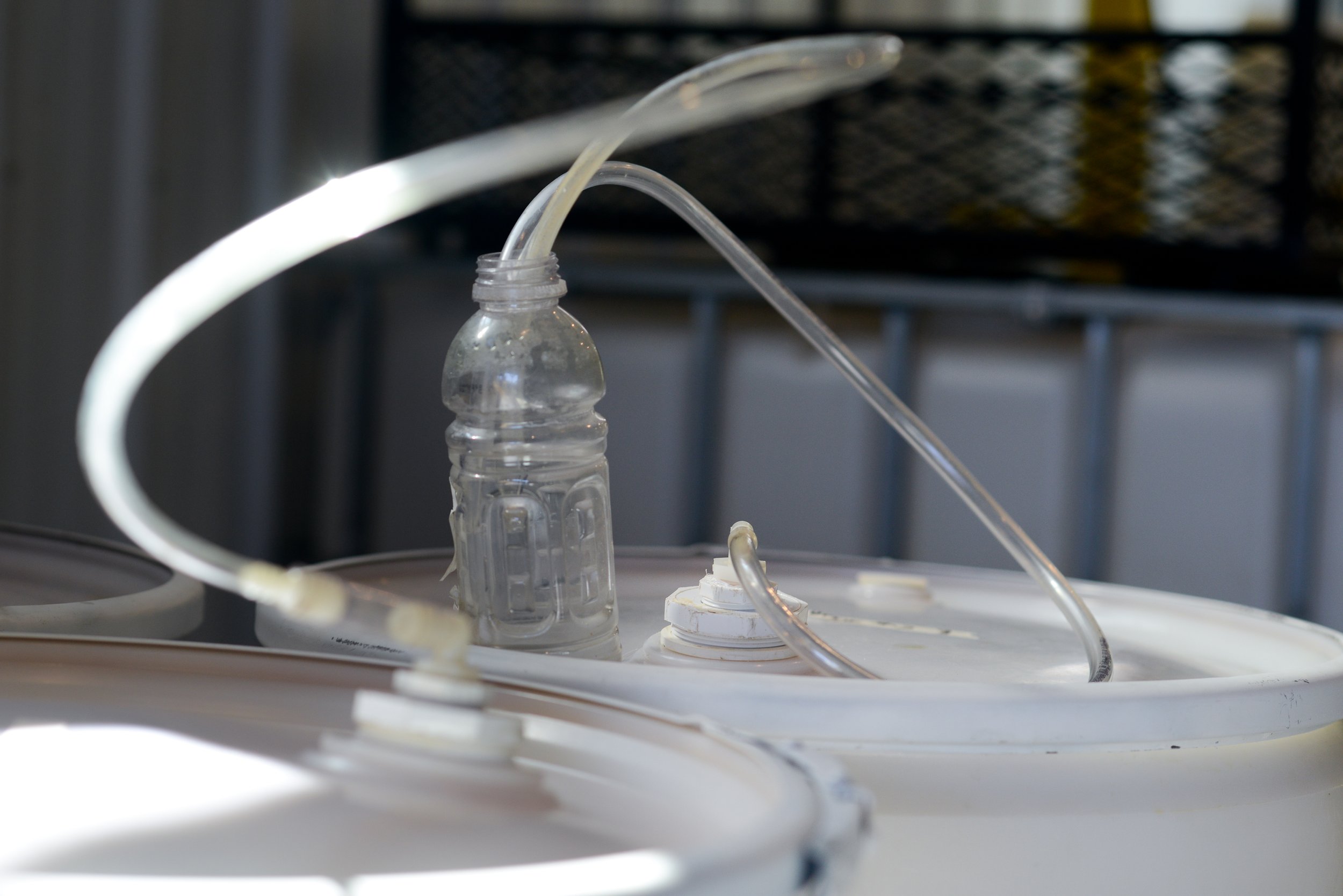

1994 was a phenomenal apple year in Highland County, and having exhausted his regular customers with fresh cider, Kirk still had bushels of apples to press. Rather than let them go to waste, he decided to try his hand at making hard cider, the section on which in all the pomology books he had devoured, he had so far ignored. “I couldn’t care less about it but it's better than just letting these apples rot,” he says.

A few months later, around the time of Monetery’s annual Maple Festival, he remembered that he had several gallon jugs of cider in his basement that had lain forgotten, he shared it with friends, and discovered that he had made something special.

“Once you get a buzz from something you’ve made, you’re hooked for life,” Kirk says ”Every year after that I made a little hard cider”.

Fast forward a couple of decades, and having attended cider makers’ forums hosted by Chuck Shelton of Albemarle CiderWorks, as well as buying trees from them, in 2015 Kirk made the decision to start Big Fish Cider.

“We’re similar in that we prefer clean ferments of traditional American cider apples,” Chuck tells me. “My preference is for clean, dry, crisp ciders. Kirk prefers ciders that are a little softer on the palate and has, very capably, incorporated some other flavors, such as ginger, local honey, and maple syrup.”

“These subtle differences notwithstanding, Big Fish ciders are the closest in Virginia to ours at Albemarle CiderWorks. I can easily find one of his ciders to drink and enjoy,” he adds.

Kirk opened the Big Fish cidery and tasting room in 2016, in a building that at one time was a local cinema, upon which sits a giant neon trout, dating from the 1960s, from which the cidery takes its name.

As well as owning a pair of their own orchards, Big Fish also harvest from a third that was laid out by Virginia’s legendary pomologist, Tom Burford. They also take advantage of being in a part of the world where having a handful of apple trees is pretty much the norm, and cattle ranches boast 60 foot high wilding apple trees, varieties unknown. Each year they release Highland Scrumpy, a cider made originally from apples donated by locals in a massive apple drive, but carefully made with fruit from specific trees that have shown the required characteristics to make great cider.

It’s this commitment to using locally grown apples that has presented Kirk, and other cider makers in the same area with a problem. While it’s true that old time wisdom in the mountains says that an orchard having two good years in five is doing well, the onset of climate change could render this formerly reliable way of thinking obsolete.

***

The winter of 2022-23 was abnormally mild, in the US we follow the meteorological seasons, with winter starting at the winter solstice and lasting until the spring equinox in March. With nighttime temperatures rarely getting below freezing, and daytime highs regularly getting above 50° Fahrenheit, (that’s 10° Celsius.) In more normal years, high and low temperatures hover around freezing, giving apple trees the dormancy and chill hours they need to produce fruit.

In the presence of a significantly milder winter the apple trees up and down the Alleghenies came into blossom in mid April, several weeks earlier than usual. One of the quirks of Virginia weather is that early spring cold snaps are nothing unusual. Gardeners, orchardists, and farmers throughout the state know better than to trust the spring weather.

““We’re similar in that we prefer clean ferments of traditional American cider apples.””

However, where just a few weeks earlier the mountains were awash with the white of apple blossom, on the first weekend of May last year, arctic air poured over the hills, bringing with it several inches of snow, into the narrow valleys and hollers, killing off an estimated 90 to 95% of the fruit that had set prematurely.

“If it wasn’t for the wild apples, it would have been our worst year ever,” Kirk tells me.

Trees at the highest elevations survived largely unscathed as the frigid air sank into the valleys, and it was these trees, predominantly heirloom and seedling varieties, better adapted to growing at height, that saw bumper crops, in large part because the cold wiped out the food that the insect colonies rely upon.

“We don’t shoot for consistency,” Kirk says. “We take whatever Mother Nature gives us as far as apples, and I don’t try to manipulate the flavour, or the acid.”

Cider, in common with any artisanal agricultural product, is very much at the mercy of the climate. As winters become milder and wetter in places like Highland County, the threat of crop destruction by sudden swings in temperature at an inopportune moment is very real. Making quality cider is not simply a case of pressing any old apple and letting it ferment, the fruit needs appropriate levels of sugar, tannins, and acid, the kind of levels found in heirloom varieties not modified for the supermarket shelf. As one legendary figure in Virginian cider history, Diane Flynt of Foggy Ridge Orchards, tells me: “it’s one thing to grow cider apples, it is quite another to grow apples for cider.”

At Big Fish Cider, Kirk Billingsley couldn’t imagine making cider with any other apples than those of Highland County, and so we can only hope that the old wisdom of two good harvests in five years holds. If said wisdom remains true, ciders like those from Big Fish will continue the tradition of mountain ciders, despite the challenges arising from the onset of climate change.