Lost Wines and Funky Treasures with Andrew Nielsen of Le Grappin

Saint-Amour is a wine ruined by its name.

It translates roughly to Saint of Love in English. A century ago the wines of the Saint-Amour appellation were considered amongst the best in Beaujolais and commanded prices comparable to more pedigreed Burgundy wines. But as Valentines Day became increasingly commercialised, Saint-Amour winemakers saw their sales telescoped into one night of the year. Wine made in September was gone by February. Before long no one cared whether the wine was good, all that mattered was the label.

“It's going to be on a prix-fixe menu and frankly everyone's just looking to get a shag,” winemaker Andrew Nielsen tells me.

With sales uncoupled from quality, winemakers caved to commercial pressure and cut corners in the vineyards and the cellar. Once the ensuing downward spiral of higher yields chasing falling prices had exhausted the vines and turned the soil to dust, Saint-Amour’s fall from grace was complete.

Andrew tells this story because he cares about this wine. He is a man of big passions: he loves fermentation, flavour and terroir. He cares about quality, from the soil up. He wants to grow the best vines to get the best grapes to make the finest wine he can.

But it’s not simply a case of making good wine. Nielsen, who runs Le Grappin winery with his wife Emma, wants to rediscover forgotten wines like Saint-Amour and rebuild their lost reputations. “That's the kind of thing I'm excited about,” he says. “We wanted to show off these smaller, less appreciated areas and show that they can tell an interesting story.”

Illustrations by James Albon

To do this, he seeks out parcels—small corners of larger vineyards—that have been forgotten by the wine world and picks growers thirsty for change. He encourages them to forego pesticides and herbicides and use organic farming methods instead. And he pays above the odds for their grapes to break the cycle of decline.

Andrew has seen this approach bear fruit. “All of a sudden there's worms back in the soil, you can see ladybug larvae, all of these things that just weren't there,” he says.

And this return to life shows in the wine. Their 2017 Saint-Amour—released under the Du Grappin range of refreshing and unpretentious vins de soif, or drinking wines—bursts with redcurrant, cherry and bubblegum; it has cloves and mushroom-earthy undertones. As I pull the cork I feel I’m playing a small but important part as the final link in a chain that’s driving the renaissance of a vineyard.

Andrew, an Australian, found his passion for wine in California working a vintage with Pinot Noir and Chardonnay specialists Kosta Browne. Harvests alongside some of the industry’s great winemakers in New Zealand’s Central Otago and the Yarra Valley in Australia followed before settling in Burgundy. He now splits his time between England and France, spending part of the year in South East London and the rest in the medieval walled town of Beaune, the wine capital of Burgundy.

““It’s going to be on a prix-fixe menu and frankly everyone’s just looking to get a shag.””

Talking to Andrew it’s easy to see how much he loves fermentation. It’s not just that he can recall the names of obscure yeasts in the same way others might list contestants on their favourite reality TV show. It’s an animation that comes over him and the way he makes a complex subject relatable. Even with terms like “anaerobic environment” or “intracellular enzymatic reaction” floating around, our conversation isn’t dry or technical. Instead, I taste the grapes bursting with juice within the darkness of the closed tanks; I smell the fruity bubblegum aromas in my mind; I see the wine running bright.

His passion for yeast’s magic isn’t limited to wine. Andrew has made sauerkraut and kimchi. He has brewed beer, and cider using apples from his garden. He’s even tried making cheese, although that ended in disaster. “I have so many friends making great cheese. I’d rather buy theirs,” he says.

Andrew made these friends working at Neal’s Yard Dairy, based in London’s Borough Market, where he sold cheese while studying for his viticulture degree. For five years he ran regular tasting evenings, pairing cheese with beer, wine and cider. “I still think beer is a better match with cheese than a lot of wine is,” he says.

It was there that Andrew got to know Evin O’Riordain, who also worked for a spell at Neal’s Yard before moving on to establish The Kernel Brewery in 2009. Evin and his colleagues drink “a goodly amount“ of Le Grappin’s wines. Andrew, in turn, shuttles van-loads of Kernel beer over to Beaune every year to share with friends, to appease locals and to lubricate the harvest.

“[Andrew] forms part of our extended family so working with him is a natural extension of how we do things,” Evin says. “We share similar standards and a similar approach to quality and community.”

With Andrew’s ties to the beer world, it was perhaps inevitable that he would sell barrels to brewers. “I just saw the state of the barrels that brewers were able to get their hands on and I thought oh my God, I wouldn't put beer in that,” he tells me.

It was Evin who first bought wine barrels from Le Grappin, back in 2012. Word spread and soon Andrew was sending barrels to the likes of Thornbridge, Partizan, Cloudwater and Burning Sky.

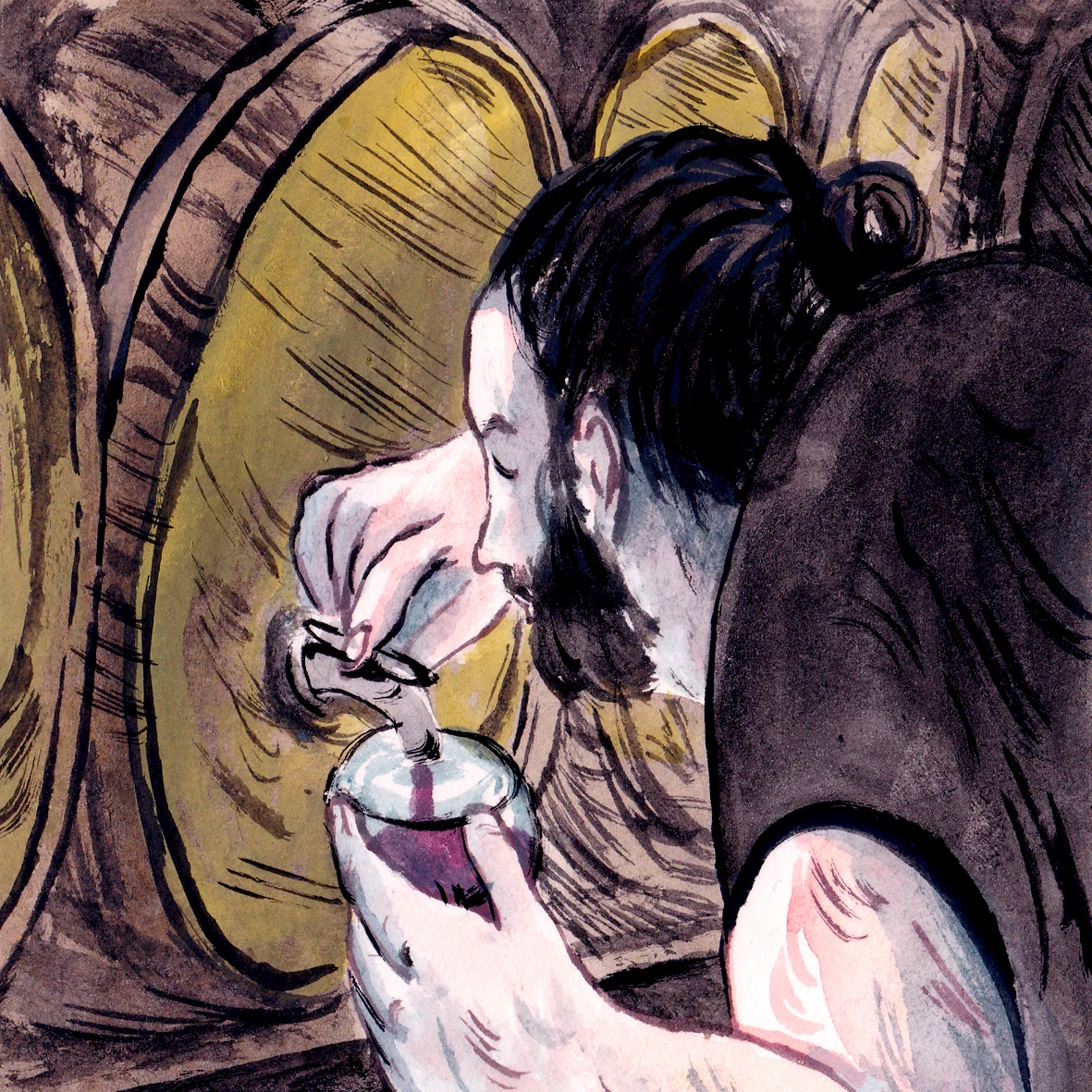

At a time when many barrels on the market were spoiled, Andrew decided he would only offer barrels from winegrowers he knew himself and trusted. “Our barrels are not the cheapest, but I am working with great winemakers and I'm only buying the best. I’ve smelled them. I've looked at them. They're good barrels.”

He also convinced the winemakers to leave their lees—sediment of yeast, bacteria and other particulates—inside: “You can wash that out if you want, but there's all of this bacteria and yeast and wine flavours in there, all these goodies if you want them.”

Andrew’s biggest customer is James Bardgett at the Wild Beer Co. in Somerset. “We must have bought over 400 barrels from him by now, which is nearly half of our complete collection,” James says. “His barrels play a big part in the flavours of our flagship beer, Modus Operandi. The acidity of the beer is mostly from the bacteria in the barrels. They are always superb quality.”

Returning to wine, I ask Andrew what makes a good winemaker. He opts for humility in the face of nature: “You shouldn't be afraid to embrace what the vintage gives you.”

““You shouldn’t be afraid to embrace what the vintage gives you.””

He tells me about working with a parcel of Chardonnay in Les Gravières, perhaps the most respected and famous premier cru site in the Santenay region of the Côte de Beaune. In the first year, he felt the wine was going to be big, so he did what he could to rein it in. He gave the juice less contact with the grapes’ skins and stems than he would normally and used older barrels for ageing the wine.

“The wine was nice, but it just didn't feel like it had another year to me,” he says, concerned that it wouldn’t age well. In the second year, it was big again. “And I was like, okay, you want to be big? Let's roll with it. And that's when I really saw the wine go from good to wow.”

This focus on vintages unearths something I have often felt but not yet articulated: a fascination with the way wine is so bound to the year in which it is made. Brewers make beer day in, day out. There’s always more malt and more time for another boil. But for winemakers, there is just one growth each year; one harvest; one chance to make wine. It is bittersweet how winemakers spend so little time doing what they love. I ask Andrew whether he sees it this way.

“I try not to!” he laughs. “I’ve probably only got 20 more harvests in me if I’m lucky. I'm 45, you know. Who knows how you are in 20 years?”

Despite only having that one chance each year he says winemakers are lucky. “Wine would be impossible [to make] if we didn't have more room to make mistakes than with beer or cheese or in the kitchen. If you overcook a steak, you’ve overcooked that steak. If you leave the grapes on the skins for an extra three days that doesn't mean a ruined wine, it just means a different style of wine.”