Shawarma Saturdays — Reaching for Home During a Pandemic

Growing up in Bahrain there were aspects of my childhood that now seem dreamy. Swimming outdoors in crystal pools, palm trees rustling overhead. Camping at the jebel, hunting out ancient shark teeth from when the desert was sea-bed. We lived in gated compounds watched over by security guards; gangs of children ran riot through the scent of jasmine and bougainvillea.

The word I use to talk about that experience is “expat”. The vocabulary of migration is complex and loaded, but this is the word that best encompasses my life in Bahrain. Expats have bars in their houses stocked with imported gin. They have burnt skin and memberships to the British, Yacht, and Rugby Clubs. They send their children to private schools and are always, eventually, going home.

There are aspects of my upbringing I used to hide. I attempted for years to take on the soft rolling rrr of Scotland’s central belt and valiantly tried to remember the correct pronunciation of oregano. Now, I lean into the differences in my pan-Atlantic accent. I grew up abroad. There are consequences.

Holidays were duty trips to the UK to visit relatives, and these are the trips my parents still have to navigate each summer. Well, most summers.

***

It takes less than ten hours, including a layover, to travel from my cottage in Scotland to my parents’ house in Bahrain. One heady weekend in the early aughts my parents travelled to Stirling for a single night to see our favourite band play—a cèilidh band called Rusty Nail—in our favourite pub. They were tired but elated on the turnaround.

““I have tried the mess that is a British kebab only once. Once was enough.””

I go back less often now that I have a toddler and a mortgage. The foods I seek out on visits to the “sand-pit”, as the country is affectionately known, are the things it’s difficult to get right elsewhere. Labneh bread, pillowy hummus. Sticky dates. Lemon-mint juice, hold the sugar. Shawarma.

My friends from school are now scattered across the globe, third culture kids who belong everywhere and nowhere. Some returned to Bahrain after university, lured by the easy lifestyle and tight connectivity. I asked on a certain social media platform for their memories of shawarma and heard from people living in Norway, Zimbabwe, and New Zealand.

Pip still lives in Bahrain and works in Saudi, and says shawarma is what defines the Middle East. Tarik from California and Rania from Canada—neither can find shawarma to rival the İskender kebab from Al Abraaj. Jonny in Nottingham claims Bahrain’s shawarma was “the greatest culinary experience of my life.”

As teenagers, we fibbed our way into JJ’s, the mahogany-dark Irish bar in Adliyah. We drank until 1am then stumbled around to Shawarma Alley, a strip of ramshackle restaurants and serving counters open from breakfast till bedtime, hunting a drunken snack. These were nothing like the kebabs found up and down the UK. On paper, they are both spit-roasted meats, sliced into bread with sauce and vegetables, in reality, they are nothing alike. I have tried the mess that is a British kebab only once. Once was enough.

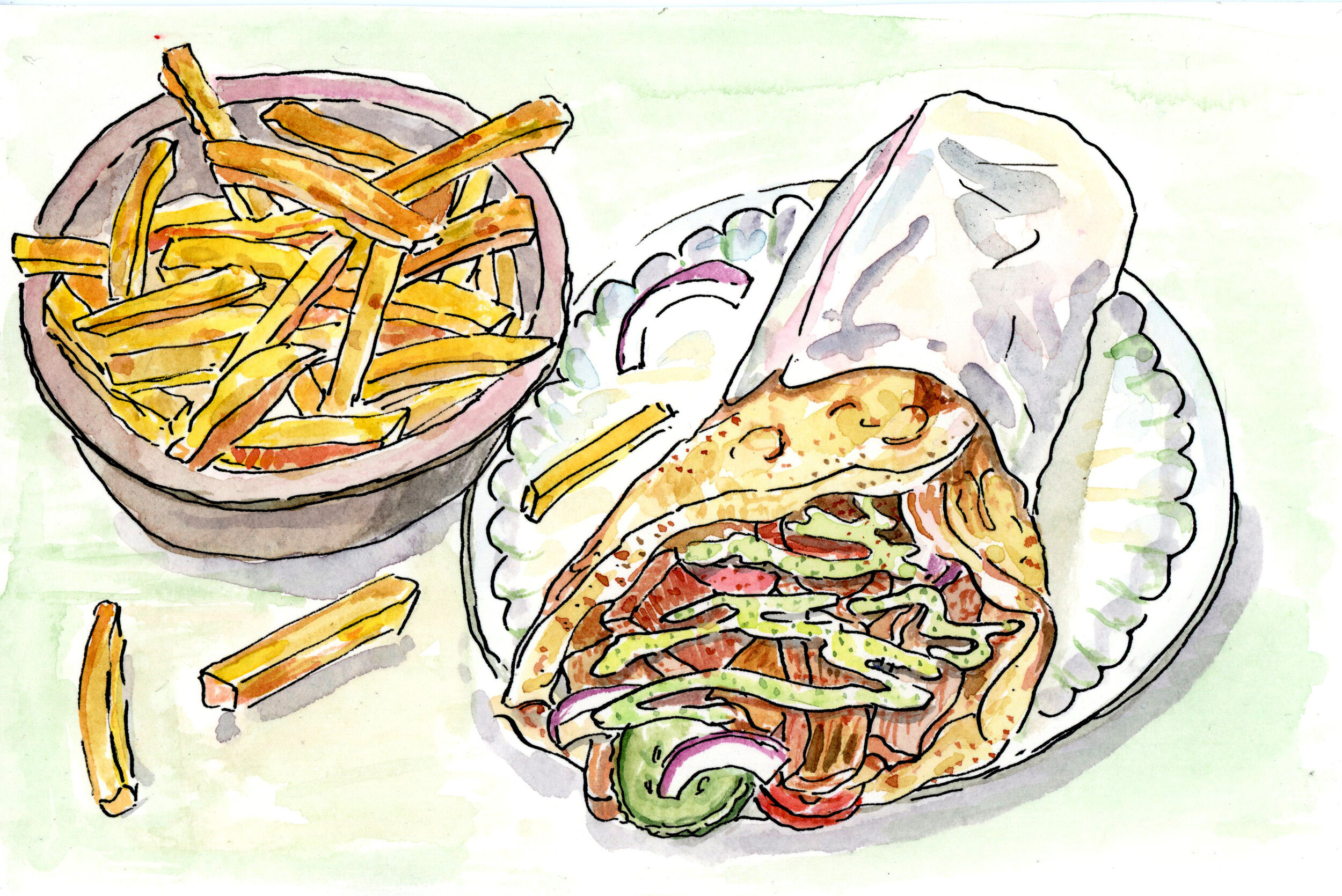

True shawarma comes on Lebanese bread: soft, floury, gently pouffy. Unlike a burrito, where the excess tortilla is tucked into itself like a well-made bed, the shawarma is simply coaxed together. Unwrap the greaseproof paper and the bread will unfurl, perfect for splashing in hot sauce.

Illustrations by Helen Hugh-Jones

The filling is roasted slowly, most often in front of electric grills but sometimes over charcoal. The options are chicken, beef or ‘meat’ (mutton, hopefully), all carefully spiced. Strips are cut from the spit with serrated knives as long as my torso, steadied by the back of a serving spoon and a confident hand.

I like pickle, shredded lettuce, and tomato on mine; and chips—always chips. My mum and dad pick them out but I absolutely need those rogue chips, soft and soggy from the heat. They are as essential to my shawarma experience as the tahina and garlic sauces.

***

The landscape of my childhood doesn’t really exist today. There is a racing track where once there were bedouin [an ethnic group of nomadic Arabs]. Bab al Bahrain—the entrance to the souq [street market]—is clean and air-conditioned. Bahrain’s landmass has grown by 11% since the 80s, the coastline ever-shifting as sand is dragged up from the sea. Amwaj is one of the communities built on new land, luxurious villas and blocks of apartments on a canal system centred around an artificial lagoon.

When my parents moved to Amwaj, Shawarma Saturdays became an institution. The doors were flung open to friends of many years and to new acquaintances alike. Around the fire pit were Hash House Harriers, American marines, my teachers. Everyone was welcome.

Kilos of meat and chicken shawarma were delivered in plastic carrier bags still steaming, along with, following my fall into vegetarianism, a couple of falafel wraps for me. The sandwiches were doused in mango hot sauce while we doused ourselves in Coors Lite.

““Shawarma is not just a sandwich.””

My brother is at boarding school in the south of England, and when he goes home he requests shawarma as his first and last meals. I have known my parents to travel to visit him with a bag of shawarma stuffed in next to their toiletries and socks.

He has not had shawarma in nearly a year. His school was one of the first to announce closure and instead of risking a harsh quarantine by travelling to Bahrain at the start of lockdown, he came to live with me. I drove eight hours each way to pick him up rather than let him travel by bus and train and tube and plane when we weren’t certain what the risks were and there was not yet risk-mitigation in place.

My father fell seriously ill in May last year. In any other year, I would have jumped on a plane immediately and been there within 24 hours. In 2020, my sixteen-year-old brother and I paced my cottage red-eyed, checking every few minutes for texts from our mum. For the first time in our lives, Bahrain—home—was out of reach.

In this strange past year, and especially during that worry-filled time in the spring and summer when my father was in the hospital, my thoughts have returned more often to shawarma, to what it represents.

Shawarma is not just a sandwich. It’s the feeling of greased paper tearing in a straight line as I laugh at an in-joke. It’s the garlic and tahina, soft on the tongue. It’s weak beer and wood-smoke in the bosom of my family. It’s home.

It may be out of reach for now, but if we stay patient and stay safe, I—and the hundreds of thousands of people living away from their families—will be able to go home again. That shawarma is going to taste so sweet.