Kōji, Culture, and Community, Part 3 — Soy Sauce, Enzymes, and Transnationalism

Am I a soy sauce nationalist?

Olive oil, sesame oil, salt, pepper, MSG, and soy sauce; these are the mainstays of my kitchen counter, the core line-up of playable characters that can be called upon to unleash an unstoppable combo attack against blandness. For the most part, the provenance of these ingredients is unimportant to me—but the soy sauce is always, and always has been, Japanese.

My soy sauce is always all-purpose koikuchi shōyu, to be specific. I’ve got backup in the cupboards: nama (unpasteurised), marudaizu (whole soybean) usukuchi (light), tamari (heavy), and for special occasions, some rare, three year aged kioke (wooden barrel-aged). I even have a few obscure Japanese seafood-based shōyu-adjacent products—salmon and squid gyoshō and some hishio made with sea urchin.

It’s not that I’m opposed to the soy sauces of other countries. It’s more that it hardly even occurs to me that they exist. It’s definitely fair to say that I have a parochial soy sauce worldview.

It begs the question: why?

How did I end up with that little bottle of Kikkoman, forever nestled next to the utensil pot? And it is always a Kikkoman bottle, even if the soy sauce inside isn’t—I refill it with whatever brand I have on hand, but the bottle itself is just too perfectly engineered to resist. It was originally produced by the late Kenji Ekuan, one of Japan’s most celebrated designers, who also developed the Narita Express and Komachi shinkansen trains, as well as the beautiful Tokyo Metropolitan Government logo.

The Kikkoman bottle is a masterpiece, instantly recognisable and a joy to use. Ekuan was driven to create such wonderful objects after witnessing the unbearable destruction of the atomic bomb dropped on his hometown, Hiroshima. In an NHK interview, Ekuan explained how he channelled his grief into a creative force:

“Faced with brutal nothingness, I felt a great nostalgia for something to touch, something to look at,” he said. “The existence of tangible things is important. It's evidence that we're here as human beings.”

Ekuan’s design is so perfect that it feels like something that has simply always existed. It has inspired countless imitators, but none of them have the same effortless elegance.

***

I became interested in Japanese food when I was a teenager, but my family had been cooking with Kikkoman long before that. Probably because there’s been a Kikkoman factory in Walworth, Wisconsin since 1973, about an hour’s drive from my childhood home. Kikkoman chose Wisconsin as a production site for its geographic centrality within North America, for our abundance of soybeans and wheat, and for our (apparently) world-famous protestant work ethic.

The factory was built at a time when midwestern attitudes towards Japan were generally hostile, due to what was perceived as an erosion of the American manufacturing economy by Japanese competition, especially in the auto industry. But Kikkoman quickly endeared themselves to the citizens of Walworth by creating job opportunities for local workers, and by staying true to an ethos of ‘coexistence and co-prosperity.’

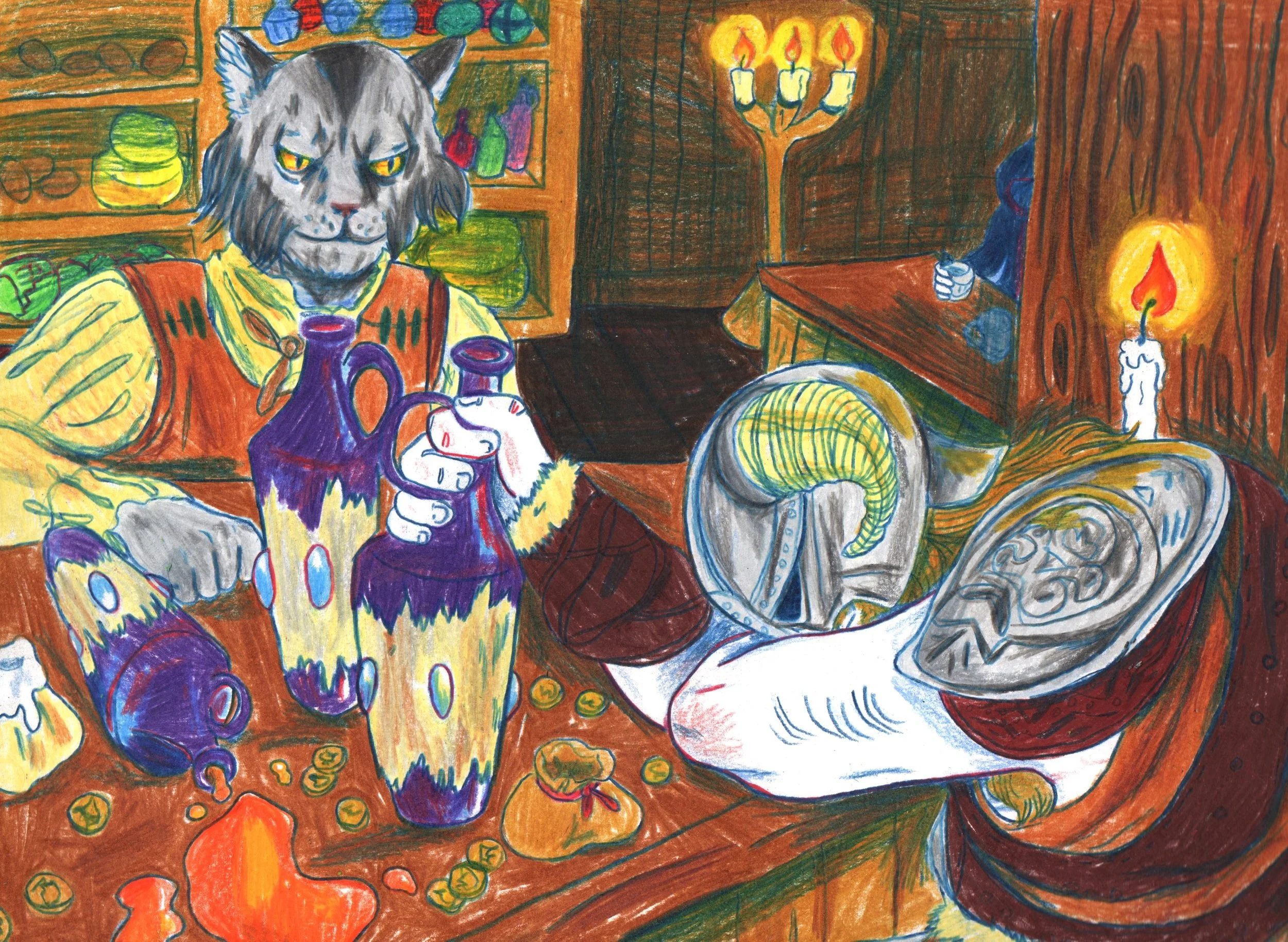

Illustrations by Zhigang Zhang

Writing for Artful Living, Brittany Chaffee reported that employees from Japan and Wisconsin came together at cookouts to eat bratwurst and drink sake, and that locals quickly acquired a taste for the once-foreign condiment. One production manager apparently came to love Kikkoman so much he put it on his peaches, and a local minister was known to drizzle it onto ice cream. By the time I was a kid, in the mid-90s, soy sauce was as familiar to us Wisconsinites as Merkt’s cheese or Miller High Life.

My personal preference for Japanese soy sauce (and Kikkoman specifically) is the result of global economic shifts and waves of soft power, far beyond a simple matter of taste. Japanophilia does not exist in a vacuum.

Since the 1970s, the worldwide export of Japanese consumer goods, design, and pop culture has been a perpetual motion machine of international influence. As white-bread as my upbringing was, Japan has always had a permeating and outsized presence in my day-to-day life. The ‘80s, ‘90s, and early 2000s were the heyday of the Walkman and Discman, of Pokémon, Maruchan, Cowboy Bebop, Chrono Trigger, and Iron Chef.

In Back to the Future Part III (1990), Marty McFly put it matter-of-factly: ‘All the best stuff is made in Japan.’ In Die Hard (1988), Nakatomi president Joe Takagi said it in a far punchier, more problematic way: ‘Pearl Harbor didn’t work out, so we got you with tape decks.’

The enthusiastic acceptance of things Japanese into our everyday lives is inseparable from Japan’s economic and political positions. This interplay as it applies to food in particular has been parsed by many scholars, perhaps most thoroughly by sociologist Krishnendu Ray. He has described Japanese cuisine as similar to French cuisine in how it is considered ‘both foreign and prestigious,’ as a result of Japan’s 20th century economic ascension, and the relative affluence of Japanese expats and immigrants in the US and Europe.

But there have also been concerted efforts by the Japanese government to actively promote Japanese food abroad, partly to support the tourism and food export industries, but also as a matter of national pride. In Vittles, Jonathan Nunn notes that: ‘The Japanese were very astute to rebrand their worst nerds as ‘shokunin’ and make them sound badass… The Indian uncle has never had this rebrand, and yet they are just as annoying and obsessive.’

Today, Japan has one of the most widely accepted passports in the world, so perhaps it’s not surprising that their condiments are so widely accepted as well. And that also goes for for kōji—the culture without which most of those condiments, including soy sauce, would not exist.

***

Analogous or similar fermentation cultures can be found all across East and Southeast Asia— China has qu, Korea has nuruk, the Malay Archipelago has ragi tapai, the Philippines have bubod, etc. But none of these have taken the world by storm the same way kōji has. The fermentation internet rallies behind hashtags like #kojibuildscommunity. There are numerous English language books on kōji. And there’s even an annual online conference called Kojicon. In 2024, the kōji craze is in full swing.

““The Kikkoman bottle is a masterpiece, instantly recognisable and a joy to use.””

The dominance of kōji within fermentation discourse is partly the result of broader international Japanophilia, but that isn’t the whole story. For some perspective on the particular properties of kōji that may have made it so popular, I spoke to Haruko Uchishiba, a kōji educator based in North London operating as The Koji Fermenteria. Haruko trained under the kōji master Nakaji and has been selling kōji-based ferments and leading workshops in London since 2018.

Haruko invites me into her compact but meticulously organised kōji workshop, a repurposed utility room in her home. One of the first things I realise as we peruse her fridge full of various kōji strains is that I have fundamentally misunderstood what kōji is. I have always thought kōji refers to just one specific microbe—Japan’s ‘national fungus,’ Aspergillus oryzae.

When the word is used on its own, without qualifiers, that is generally true. But it can also refer to other species of Aspergillus used in particular ferments, such as Aspergillus luchuensis mut. Kawachii (shiro kōji), used primarily for shochu production, and Aspergillus sojae (shōyu kōji), which is used to make soy sauce. There are also, less commonly, entirely different microbes that may be called kōji, such as Monascus purpureus, more commonly known as ‘red yeast rice,’ or beni kōji (red kōji) in Japanese. Haruko herself mostly sticks to Aspergillus oryzae, but even within that species there are many variants.

Haruko initially became interested in fermentation and kōji for health reasons, but also because of her background in chemistry. She started off making her own dairy-free yoghurt out of lacto-fermented brown rice and soy milk, which at first she found frustrating because it didn’t always yield the results she hoped.

“I have always been curious about what’s going on,” she tells me. “I started to understand that this is a living creature that I’m dealing with… There is a reason if they don’t behave the way I expect. So I started to have a more collaborative attitude between me and the microbes.” She adds that keeping kōji is like having “billions of friends.”

This new mindset led Haruko to more consistent success making yoghurt, which emboldened her to take her fermentation to the next level with kōji—a ‘natural path,’ she says, but the reasons she prefers kōji are more complicated than just personal preference and cultural affinity.

For one thing, she explains, kōji (specifically Aspergillus oryzae) boasts extraordinarily high levels of enzymes, which produce a full, rounded flavour profile as well as ideal conditions for secondary fermentation. Key among these enzymes are amylase, which breaks down starch into sugar; protease, which breaks down protein into umami-rich amino acids; and lipase, which breaks down fats into aromatic compounds, resulting in complex flavours in the finished ferment.

In shōyu and miso production, kōji’s ability to produce sugars in turn fosters lactic acid bacteria and yeast, creating sourness and alcohol, which also boosts aroma. I have often described soy sauce and miso as having a ‘complete’ flavour—a balanced mixture of salt, umami, sweetness, and acidity. I never knew why until Haruko explained it to me. “That’s the beauty of enzymes,” she says.

Haruko says that kōji is ‘more sensitive’ than Chinese starters (collectively called qu) when it comes to maintaining the correct conditions for successful fermentation and requires more ‘TLC,’ because qu produces citric acid that protects the substrate from spoilage. This makes qu easier to inoculate in a wide range of environments, but it also makes the finished products more acidic, and qu doesn’t have the same enzymatic activity as kōji, so for her, the flavour of these ferments isn’t quite right.

“Kōji has the ability to produce at least a hundred different types of enzymes,’ Haruko says, “and as a result, it can be used for a variety of food applications, not just Japanese.”

This helps to explain kōji’s popularity outside of Japan, where it is now being used by chefs, food producers and home cooks to transform a huge range of ingredients. Specifically, Haruko mentions the The Noma Guide to Fermentation as being hugely influential in driving interest in kōji internationally.

Haruko mostly ferments traditional substrates like rice and soybeans, but she is not opposed to it being used in novel ways. In fact, while it may not have culinary applications, she is interested in kōji’s ability to break down waste.

“Scientists in Japan are even researching whether kōji can produce enzymes that degrade plastic,” she says. Kōji could even save the world.

***

There’s still a lot we don’t know about kōji, but our understanding of it has come a long way since the 17th century, when it was conceived of as a yōkai: a ghost. Writing in Gastronomica, historian Eric Rath explains that ‘kōji qualified as a yōkai… because although its manifestation might be predicted, the mould remained beyond human control or comprehension to the point that it might delay its arrival, fail to appear at all, or even grow malevolent.’ Nowadays, there is a wealth of literature, in Japanese and English, that has made kōji less phantasmic and more friendly, as long as you show it, as Haruko says, a little TLC.

There isn’t nearly as much literature on qu as there is on kōji. After chatting with a few fermentation geeks on Instagram, I got the impression that qu is more arcane—not as well documented and not as well understood. But there are some qu champions out there, one of whom is Pao-Yu Liu, a Taipei-born, East London-based fermenter who until recently operated the pickle business Pao Pop N Pickles (easily one of the most fun-to-say small business names I’ve ever heard).

Pao invited me into her production space to discuss the finer points of soy sauce, kōji, and qu, and we began with a tasting of various soy sauces—some made by her, others by friends in the fermentation scene, and a few commercially brewed varieties from Taiwan, Japan, the US and the UK.

““People keep saying they’re experts, and like… they’re just doing another umeboshi! Why is everyone just doing one thing?””

The flavours were astonishing—delicious and incredibly diverse. It was like seeing the soy sauce world in colour for the first time. Some were light and fruity, like salted tomato juice, while others had a flavour of caramelised nuts. My favourite one tasted like a rich, velvety imperial stout, but with a slight sourness, like something brewed by Belgium’s De Struise. It was from a Taiwanese company, and made with black soybeans, sugar, and red kōji, or âng-khak in Hokkien. None of these ingredients are typically used in Japanese soy sauce production. I couldn’t believe how much I had been missing.

Pao says that one reason Japanese kōji may have caught on with so many fermenters is because its usage is more codified, which makes it a little easier to understand.

Qu can be everything. It’s a catch-all term for a wide variety of fermentation starter cultures, containing many different microbes. “Japanese culture is so rigid, and everything has rules,” Pao says. “And people love that!”

From Pao’s perspective, when the parameters of the process are clearly defined, it makes everything simpler and increases the chances of a successful ferment. But sometimes Pao is exasperated by discussions of what is or isn’t correct when it comes to kōji-based products, especially with regards to what can be called ‘shōyu’ or not.

“For god’s sake!” she laughs, “the word “shōyu” comes from Chinese… jiàngyóu!” In her view, we shouldn’t be too precious about what we put in our soy sauce or what we call it, because these things have historically always been fluid and dynamic, changing over time and geography. She points out that Taiwanese fermentation culture draws on Chinese, Japanese, and indigenous traditions, and as a result, it’s not so strictly regimented.

Pao’s approach is creative and experimental—she has made a miso out of leftover lasagna, and a remarkable fish sauce-like product out of fish soup. Like a lot of fermenters, she got started off with lactobacillus and kōji, mostly due to the wealth of availability of information about them. “There were no books on qu,” she says. But since then she has explored all sorts of other fermentation and preservation methods, including an incredible way of making tofuru without the typical âng-khak or kōji as a starter.

“In Yilan, they found out they can use pineapple, because pineapple contains loads of enzymes,” Pao says, and she’s recreated this in her workshop. The result is incredible—the pineapple’s enzymes have made the tofu rich, creamy, and dense, while heightening its own sweetness. It tastes like a cheese and pineapple hedgehog if you ate it after dropping acid.

Now that Pao has wrapped up her commercial pickle production, she says she’d like to teach, but also to travel, to learn more about the whole world of fermentation.

“I want people to know there’s so much more… there’s so much I don’t know! People keep saying they’re experts, and like… they’re just doing another umeboshi! Why is everyone just doing one thing?” she laughs. “People aren’t really thinking outside the box. They’re just following the same patterns.”

I left Pao’s workshop thinking about how she’s right: there’s so little I know, so much to learn, so many soy sauces to try, from so many places. The world is big and fascinating, and we should engage with all of it. I search online to see if I can order that Taiwanese soy sauce I was so enamoured with. I cannot. Oh well. Later, I make dinner, with a drizzle of shōyu from the Kikkoman bottle, as always. I think nothing of it.

There’s a classic episode of The Simpsons where Homer eats poisonous fugu at a sushi restaurant, and is subsequently told he has 24 hours left to live. When the prognosis turns out to be false, Homer is born again; he leaps from his armchair, shouting, ‘I'm alive, and I couldn't be happier! From this day forward, I vow to live life to its fullest!’

As the credits roll, Homer is on the sofa, mindlessly chomping on pork rinds as he watches a bowling match on TV. It is a brutal moment of television, an indictment of us all. Homer has his snacks and sports. I have my Kikkoman on the countertop.