The Boar They Butchered — The Demise of Ringwood Brewery, Hampshire

I don’t remember my first pint of Ringwood Best Bitter, but I would put good money on it being at The Royal Oak in Fritham, a hamlet in the New Forest National Park.

We used to go to The Royal Oak a lot as a family. It's the picture-perfect country pub—thatched roof, three tiny rooms, surrounded by trees. Wild ponies and pigs wander around outside, while inside regulars talk about nothing in particular to each other, or to the owners of 26 years, Neil and Pauline McCulloch, who run it with their daughter Cathy.

“ If you're soaking wet and you've got a soaking wet dog and muddy boots, you can just walk in. Just come in and be welcome,” Neil says.

His philosophy is this: “Just keep things straightforward and simple… you can come here this year and you can come here next year and not a huge amount would have changed.”

By the time I was old enough to start drinking in pubs, I’d been introduced to real ale by my Dad. Ringwood Best Bitter fuelled my conversion.

“We would have eight barrels behind the bar, of which four of those at any one time would be Ringwood Best,” Neil says. “The quality of their beer was just second to none.”

““...there’s an argument that Ringwood Brewery was the most important British brewery of the past two decades.””

He remembers a close relationship with the brewery, just 10 miles away, and its then-owner David Welsh. Even though the brewery owned a handful of pubs itself, Welsh would bring clients to The Royal Oak to showcase his beer. Neil says Ringwood even modelled some of its pubs after his own.

“We could sell as much Ringwood as you like,” Neil says. “Just before he sold it, our barrelage that year would have been 200 brewers barrels just of Ringwood products.”

That was 2007, when Marston’s bought the brewery from David Welsh for £19.2 millon.

“Something changed within the production, and the quality just plummeted,” Neil says.

Nowadays, you’ll still see plenty of beers from other regional brewers at The Royal Oak, such as Upham, Flack’s, Hop Back, Downton or Bowman. But they haven’t had a barrel of Ringwood on for years.

***

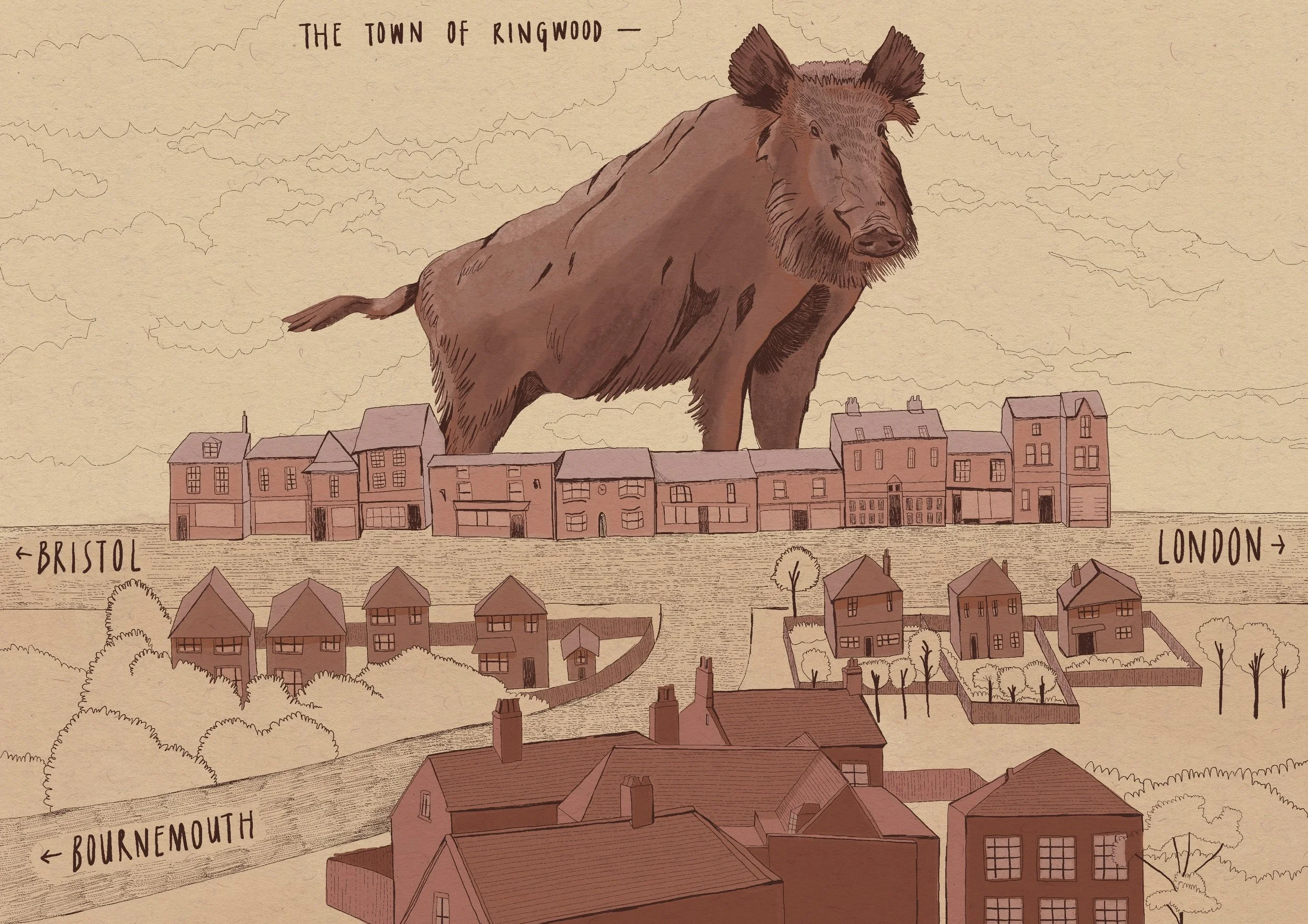

The market town of Ringwood sits on the Hampshire-Dorset border. Its brewery’s identity was firmly in the forest to its east. The logo, a boar, was a nod to the animals which roam freely in the National Park. In the early days, Ringwood beer was only sold to free houses in the New Forest—nearly all of the pubs in the towns were tied to big breweries.

But its influence stretches across Britain and far beyond. In fact, there’s an argument that Ringwood Brewery was the most important British brewery of the past two decades.

In 1978, veteran brewer Peter Austin was approaching retirement, but he had one last project in him. This was a time when the industry was dominated by the Big Six brewers—Allied Breweries (Tetley, Ansells and Ind Coope), Bass Charrington, Courage, Scottish & Newcastle, Whitbread and Watney Mann.—producing low-quality froth. In the face of this he decided to set up a new microbrewery. (Austin would go on to become the founding chairman of the Small Independent Brewers’ Association, now the Society of Independent Brewers and Associates, or SIBA.)

Through his dogged advocacy for real ale and his KISS (keep it simple, stupid) philosophy, Austin changed the beer world. Along with creating award-winning beers such as Old Thumper, Fortyniner and Best Bitter, he helped found over a hundred breweries around the world. He was a pioneer of the modern microbrewery movement.

“[Peter] really is truly the godfather of the whole thing,” says Alan Pugsley, one of Austin’s most successful protégés and now a brewery consultant in the US.

Alan remembers his job interview, in late 1981, well. A recent graduate and with no brewing experience, he dressed in a three-piece suit. He was told to wait for Austin at the train station.

Illustrations by Laurel Molly

“This fellow comes walking towards me in a light blue smock and what turned out to be yeast-stained trousers, and hair a-flying,” Alan says. “[He said] ‘come on, dear boy, we got things to do.’ And that was the beginning.” The interview took place over a beer at a local pub. It was 11 o’clock in the morning.

Alan calls himself a disciple of Austin. He paints a picture of those early days, of a small team of passionate brewers experimenting, disagreeing, improving and crafting simple, traditional British beers, which they loved. Taste was everything.

Very early on in his career, Alan was asked by Austin to help set up a separate consultancy business. Alan estimates that between them, they helped the founders of around 150 different breweries in countries such as France, Belgium, Nigeria and China. The Peter Austin Brick Kettle Brewing System was used in some of them.

“What we would do is drop the whole kettle, hops included, into this whirlpool and they would create a whirling factor that all the hops would settle down,” Alan says. “The wort would then filter down through the whole hops.”

Alan moved to New England in 1986 and introduced the brewing system to the East Coast of America. In 1992, he co-founded Shipyard, now one of the largest breweries in Maine. He dedicates a section of his own website to Peter Austin, attributing his own success to the maverick brewer who, in the face of the macro breweries, started a movement from which we all benefit today.

“ He really took me under his wing,” Alan says. “I completely trusted him and ultimately revered him—and considered him really as my surrogate father in many, many ways.”

***

In 1990, Peter Austin sold his share of Ringwood to David Welsh, his long-term business partner. Welsh continued running the brewery in a similar fashion. It only grew more successful, which is why Marston's was willing to pay £19.2 million for it in 2007.

“I was stood in the pub one day and I got a phone call from David Welsh saying, ‘Neil, I think I ought to tell you that I’ve sold the brewery to Marston’s,’” Neil McCulloch of The Royal Oak tells me. “I think he’d looked long and hard at where he was going to sell, and Marston’s had obviously come up with all the promises that they would carry on.”

Alan says Peter Austin would have been “ so proud” that a cask ale brewer like Marston’s had bought the brewery he founded. After all, Marston’s had successfully kept other acquisitions running, including Wychwood, Banks’s and Jennings. My early memories of Ringwood are from after the Marston’s acquisition, and the quality was still exceptional.

The decline was not immediate, but over time—Neil says the personal touch was lost in favour of a more corporate environment. “Marston's were more interested in selling you insurance, getting the price of your gas down and your rubbish disposal down than they were [selling] you beer,” he says.

The nail in the coffin was Marston’s merger with Carlsberg UK in 2020. By then, Ringwood’s association with the local area had already fallen apart. I was more likely to see its beers in a Wetherspoon’s in Nottingham, or in a supermarket in London, than in a New Forest pub. Bottling had moved to Wolverhampton. But the cask was still brewed in Ringwood, and I could still go in and get a pint. Each Christmas, the car park would be full of people collecting their mini kegs and their polypins, direct from the source.

In 2023, Carlsberg Marston’s Brewing Company (CMBC) announced Ringwood Brewery would close, with production moving to Burton and Wolverhampton. A year later, CMBC—by then solely owned by Carlsberg—announced it had stopped production of some cask ales, including Boondoggle and Old Thumper.

CAMRA called it “another example of a globally owned business wiping out UK brewing heritage,” as other Marston’s-owned breweries—Wychwood, Banks’s, Jennings—followed the same blueprint: Shut the regional breweries, centralise production, then cut cask ale output. (It was announced in February 2025 that Jennings had been revived after being bought by a local couple.)

Carlsberg Britvic, the successor to CMBC, says it understands the strength of feeling around its breweries, recognising it inherited “an important legacy of brewing British ale, and we are hugely passionate about creating a sustainable, successful future for traditional ales, like cask. We continue to brew Ringwood Razorback and Fortyniner on cask for fans of the brand to enjoy.”

A spokesperson for the company also said: “As a brewer, we are committed to brewing excellence—high-quality ales, from contemporary styles to traditional brews, are an essential part of this.” At the same time, they say the market for cask ale is not what it used to be, and they had to make cuts.

At the site of the old Ringwood Brewery a few months ago, there were still empty casks stacked up against the wall. Weeds pushed through the concrete, and the sign was obscured by untrimmed hedges. The logo was still prominent on the padlocked gate, though: A proud New Forest boar, captured mid-leap.

“ “Marston’s were more interested in selling you insurance.””

“It’s a sad end to the tale,” Neil says.

Austin died aged 92 in 2014, so we will never know what he would have made of his brewery being shut down by a mega lager corporation. He had founded it believing Britain’s brewers could make it through, inspiring a new generation which gave us today's modern beer. Now, as breweries close across the country, we could really do with a new Peter Austin.

In a weird parallel, it was a bottle of Carlsberg Special Brew which Austin was drinking during Alan’s job interview in 1981.

***

I remember my last pint of Ringwood—proper Ringwood, the stuff brewed in the New Forest—very clearly.

I thought we’d planned the final send-off perfectly. My Dad had picked up a small polypin of Best Bitter (by then renamed Razorback) from the brewery. We opened it at home, on my birthday, just before Christmas in 2023. We clinked our glasses and marked the end of an era.

But that wasn’t to be the end.

The actual final pint came as a surprise, two days later at a Wetherspoon’s in South London, located in a building which used to be a Tesco—a more appropriate setting, given what had happened to the brewery. I bought a pint, and sent a photo to the family WhatsApp group.

My eldest brother was the first to reply, his message laced with more than a little irony: “It lives on.”